Shelling echoed across Aleppo as emergency rooms filled with wounded civilians. By midday, schools and government offices across the city center were shuttered, streets were largely empty, and medical staff rested after a night of treating casualties under fire.

Authorities said Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF) attacks on residential neighborhoods, security positions, and medical facilities killed four, including a child and mother, while wounding at least nine, mostly women and children. By the morning of December 23, a fragile calm had returned, demonstrating how quickly fragile security arrangements can unravel. It was a warning about the costs of leaving Syria divided.

A Deadline Exposing the Fault Lines

Following Assad’s fall, relations between the transitional authority and SDF were governed less by strategy than by necessity. The two sides reached ad hoc understandings in limited areas, driven by immediate security pressures, including coordination during military operations or the temporary entry of Syrian army or security units into de facto SDF areas. Attempts at broader political dialogue repeatedly stalled over competing visions of sovereignty and governance.

On March 10, President Ahmad al-Sharaa and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi signed an agreement laying out a framework for integrating civilian and military institutions in northeastern Syria into the Syrian state. The agreement guarantees representation for all Syrians, affirms the Kurdish community as an integral part of the country, and calls for a nationwide ceasefire, the return of displaced people, and unified control of borders and energy resources.

Nine months later, progress remains limited. As reported, Syrian, Kurdish and Western officials were racing to show even modest movement before the year’s end, amid growing frustration over delays. Damascus proposes reorganizing roughly 50,000 SDF fighters into brigades and divisions within the Syrian army, provided they relinquish independent chains of command and open northeastern Syria to other army units.

An SDF official told Reuters, “We are closer to an agreement than ever before.” Western officials, however, acknowledged that any near-term announcement would likely focus on extending the deadline rather than completing integration. The problem, several journalists and analysts who spoke with Levant24 posit, is that such formulas fall short of full integration as stipulated in the original deal.

Decentralization or Autonomy by Another Name

At the heart of the impasse is a dispute over language and power. Wael Alwan, a political researcher at the Jusoor Center for Studies, said Damascus is not rejecting decentralization outright; it is rejecting models that hollow out the state.

“The Syrian government is currently pursuing full integration within a single state, while moving towards administrative decentralization and a more flexible governance model,” Alwan told Levant24. He argued that autonomy or federalism at this stage would “confuse all Syrians and hinder Syria’s ability to recover on the security, political, economic, and administrative fronts.”

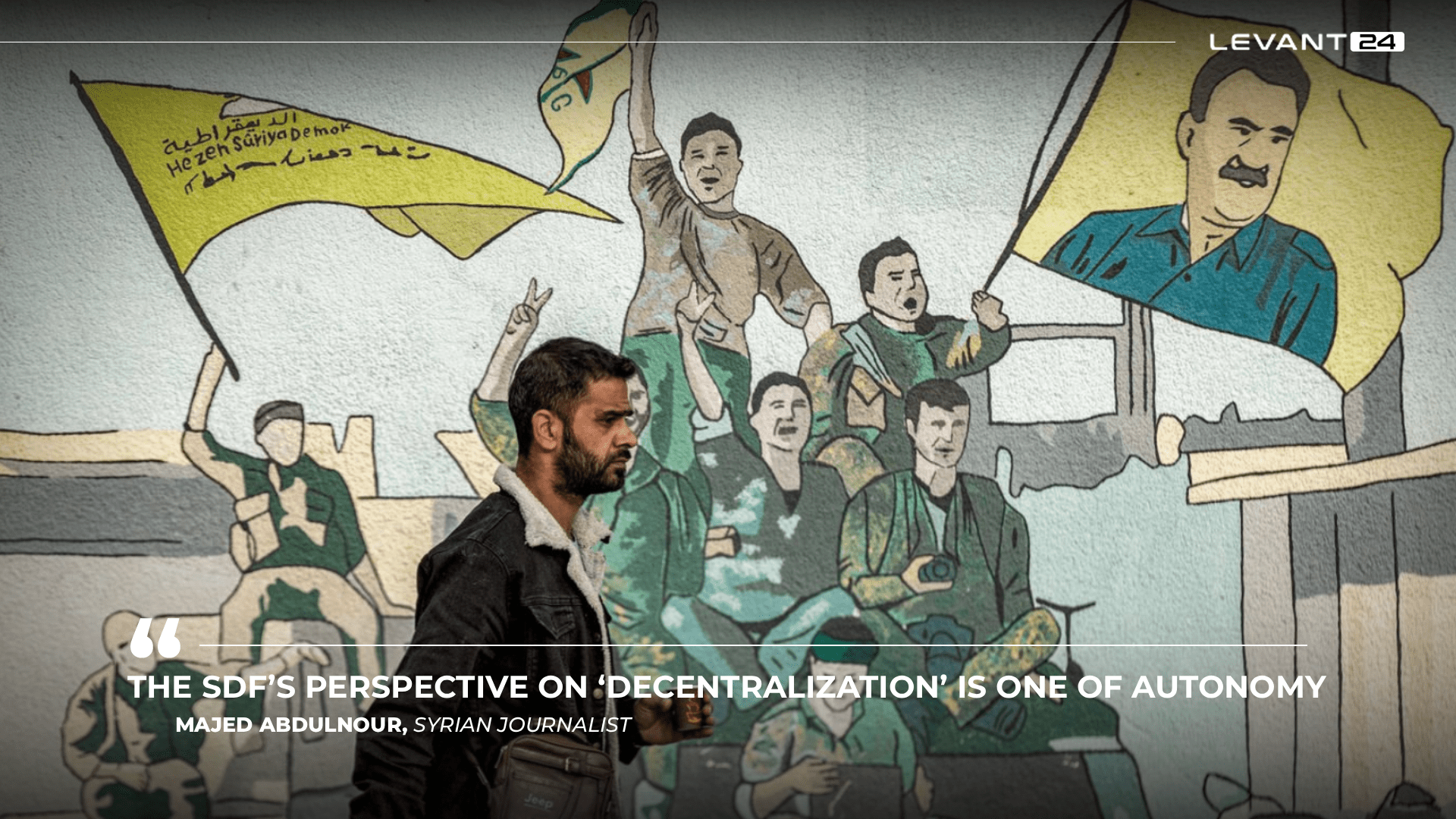

Majed Abdulnour, a Syrian journalist, framed the dispute more bluntly. “There’s a misunderstanding between Damascus and the SDF regarding the definition of decentralization,” he said to Levant24. “Damascus has no problem with administrative or expanded decentralization. However, the SDF’s perspective on ‘decentralization’ is one of autonomy.”

Abdulnour maintains that SDF demands would keep the army, police and political structures outside state control, contradicting Syria’s decentralization law and raising fears of permanent parallel rule. “Damascus will certainly not accept autonomy,” he said. “Is autonomy a precursor to secession? Or is it secession itself?”

Arab, Western and Turkish actors, notes Alwan, now back implementing the March 10 agreement as the only realistic path to stability, warning that loose federal models could open the door to “separatist or non-nationalist agendas.”

Power, Resources and the Politics of Delay

Beyond definitions lies a harder reality: control over territory brings control over wealth. Northeastern Syria holds most of the country’s oil production and large shares of its wheat and preexisting water infrastructure such as dams and pumping stations. Continued SDF dominance over these assets has direct consequences for sovereignty and reconstruction.

“The continued control of one party over a geographical region is having a significant impact on the political and economic development,” Alwan said. He warned that depriving the state of oil and gas revenues undermines national recovery and requires “real pressures, regional, international, and internal,” to ensure a fair distribution of wealth.

Abdulnour was more caustic, accusing SDF-linked elites of diverting resources for their own agendas. “In the SDF-controlled areas, development is practically nonexistent,” he said. “They are seizing existing resources, oil, agriculture, water, everything the Syrian state needs.”

Abdulnour said the delays cannot be understood without examining internal divisions within the SDF itself. “I believe there are two factions within the SDF,” he said. “One is a Syrian faction that wants to integrate into the Syrian state with demands for extensive decentralization. The other is an influential faction that dominates decision-making, namely the Workers’ Party led by Jamil Bayik, which leans toward the far right and delays the process.”

According to Abdulnour, the dominance of this second faction has allowed negotiations to stall even as pressures mount from within northeastern Syria itself. The result, he said, is a widening gap between the interests of local communities and those of a narrow leadership circle that benefits from continued separation.

That frustration is widely shared on the ground, according to Salam Hassan, a Syrian journalist from the Jazeera region of northeastern Syria. He said proposals that preserve SDF control under the guise of integration are broadly rejected by local communities. “Any integration between the Syrian Democratic Forces and the Syrian government that leaves these forces with independent control of the region is unacceptable to all components of the area, Christians, Arabs, and Kurds,” Hassan said.

Security Gaps and the Specter of ISIS

Fragmentation also carries a security cost. The fight against ISIS remains unfinished, and divided authority complicates intelligence sharing, border control, and the management of detention facilities holding tens of thousands of suspected militants and their families.

Abdulnour described the ISIS prisoners as “the trump card” in negotiations, noting that over 25,000 detainees are held in facilities under SDF control. The US fears abrupt changes could trigger escapes or a resurgence, a concern that partly explains Washington’s preference for gradualism.

Rob Geist Pinfold, a postdoctoral researcher at the Peace Research Center Prague and a lecturer in peace and security at Durham University, told Levant24 the collapse of the integration process represents Washington’s “worst nightmare.” “This has the potential to get ugly very, very fast,” he said, warning that failure could force confrontation between US partners.

Turkey, which considers the SDF’s core component, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), an extension of the PKK, has repeatedly warned against delays. Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan said Ankara’s patience was “running out,” urging the SDF to abide by the March 10 agreement and warning that alternatives to integration “will not be fruitful.”

The Cost of Parallel Rule

For Damascus, the stakes extend beyond the northeast. Large areas remaining outside state control dilute sovereignty and slow national healing after over a decade of revolution and war. They also sustain channels for foreign interference and internal destabilization.

“The state is forced to control the region for several reasons,” Abdulnour said, citing popular pressure from displaced eastern communities, the need to reclaim resources, and what he described as security concerns tied to unrest elsewhere.

Syrian officials told Reuters that the deadline for integration remains fixed and that any extension would require “irreversible steps” by the SDF.

Integration and the Risk of Drift

Syria’s recovery depends on rebuilding institutions capable of managing security, resources and political participation across the country. Administrative decentralization may offer flexibility, but only within a unified political and military framework.

Aleppo’s December clashes highlighted the risks of unresolved authority. Parallel command structures and contested security control leave ceasefires vulnerable and civilians exposed. Whether the March 10 agreement can move beyond interim arrangements toward lasting integration remains an open question, but the costs of continued fragmentation are already visible.