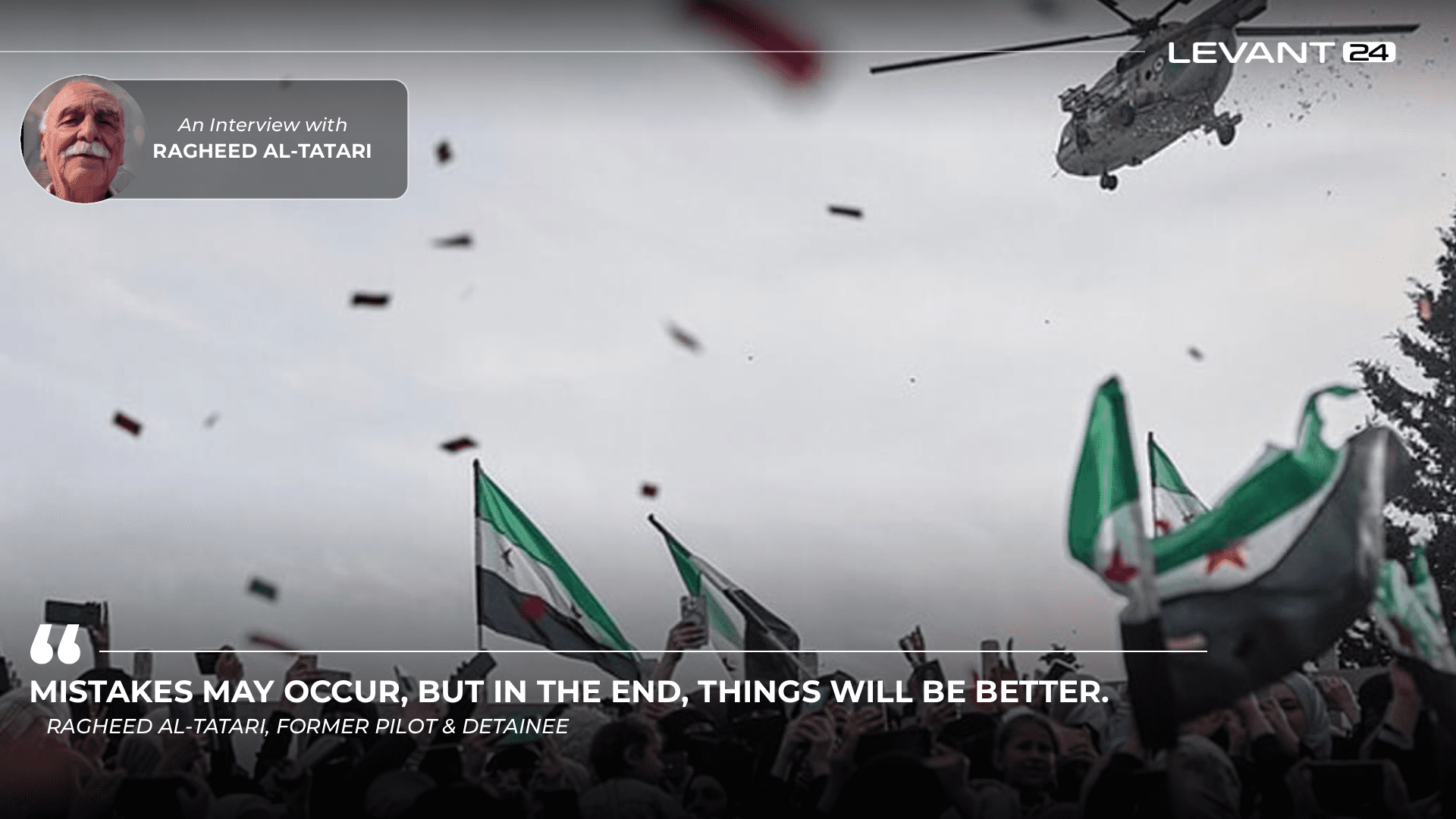

Interview with Ragheed al-Tatari, Former Pilot and Detainee

Ragheed al-Tatari, a Syrian Air Force pilot born in Damascus in 1955, spent more than forty years in the prisons of the Assad regime after being arrested in 1981 for refusing to follow military orders and encouraging others to do the same. Known as the “Dean of Syrian Detainees,” he is regarded by human rights organizations as the longest-serving political prisoner under Hafez al-Assad and his successors.

Arrested at the age of 26, Tatari endured decades of torture and transfers between some of Syria’s most notorious prisons, including Tadmor, Sednaya, and Adra. His refusal to betray fellow officers or submit to fabricated charges left him in captivity until Syria’s liberation in late 2024. Now 71, Tatari has become a living testament to both the cruelty of the Assad regime and the resilience of its victims. Levant24 spoke with him about the reasons for his arrest, the years of abuse he endured, and whether he seeks revenge or accountability after his long imprisonment.

_______________________________

Levant24: Would you please tell us the reason behind your arrest and when exactly it occurred?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “The former regime’s statements regarding detention cases have nothing to do with reality. At the beginning, I was accused of inciting disobedience to military orders, and this was the primary charge against me. However, it changed to include contact with American, Jordanian, and Egyptian authorities based on the incident of one of the pilots’ fleeing to Jordan. I was accused of these matters for a period, but the charge was changed again, as it became clear that this type of accusation would raise questions from the countries involved.

“The previous regime fabricated false information to accuse me of dealing with a foreign country, without providing any evidence or clarification for these allegations. I tried to receive answers from the lawyer, who was in charge of our case, about the fabricated information or the name of the country it was referring to, but there were no clear answers. In fact, the former regime had no real basis for these allegations, and yet I remained imprisoned. I was arrested on November 24, 1981.”

Levant24: Did you have a military trial?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “No, it wasn’t a military trial, but a civilian one. This type of trial [civilian trial] doesn’t require the presentation of evidence or specific documents. Rather, it relies primarily on the conviction of the judge alone, and perhaps even without actual conviction. You can be tried based on your sect, your city, or your place of residence. The judge who was hearing my case at that time was Suleiman al-Khatib. He wasn’t a judge or even a lawyer, he was Chief Justice.

“I was a detainee. Here, I must clarify an important point. There is a difference between a prisoner and a detainee. In prison, there are certain principles and laws that must be adhered to, while in detention, these principles are completely absent. For example, in the Tadmor and Sednaya detention centers, there are no laws protecting detainees… A detainee may be killed without anyone asking why. However, in military prisons, the situation is relatively different.”

Levant24: What types of torture were you subjected to during your time in detention?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “I was subjected to various types of torture. It’s truly difficult to describe them in words. There are deep wounds and fractures on my body, and if I describe them to you, some might think I’m exaggerating. For example, eggs were boiled and then placed hot under my armpits to break them. In addition, I was hanged from the lower back and severely beaten. This type of torture claimed the lives of many detainees and prisoners.”

Levant24: Which detention center were you held in?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “I spent three years in one of the security branches in Damascus, one year in Mazzeh Prison, 15 years in Tadmor detention center, 10 more years in Sednaya detention center, 5 years in Adra Prison, six years in Suwayda Prison, and finally three years in Tartous Prison, from which I was released December 28, 2024 (twenty days after the liberation of Syria).

Levant24: Why were you moved from one detention center to another?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “For several reasons. For example, I was moved from Tadmor detention center because it was closed at the time, and I was also moved from Adra Prison after being charged with forming an opposition group, and then I was moved to Suwayda Prison, where I managed to obtain a mobile device illegally. Finally, I ended up in Tartous Prison, from which I was released after the success of the Syrian revolution.”

Levant24: How did you manage to maintain your mental health during the years of detention?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “It was like a continuous struggle. When you’re convinced that you were walking the right path, you find strength, especially when you argue with those who detain you and find them weak and liars. I freed my mind from the prison’s constraints and imagined what was beyond those walls. I drew, carved, dedicated time to handmade works, recalled everything I had read, thought about mathematical equations, and baked.”

Levant24: Do you wish to revenge against those who imprisoned you, prefer to hold them accountable in the courts, or just seek to rebuild your new life?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “Revenge is entirely different from accountability. While revenge aims at retaliation, accountability is a positive step to ensure justice and prevent the repetition of the injustice you suffered. Holding criminals accountable has a positive impact on the entire society. Everyone who violates the law must be held accountable.

“We had never been a country of institutions… but our society during the previous regime was drowning in fear and lacked will. It is necessary to hold those responsible for violations of the law accountable. The previous regime considered itself the absolute power and the ruler had the right to do anything without restraint.”

Levant24: How do you see the future of Syria after the regime change?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “It is impossible to change everything overnight, especially after a rule that lasted 55 years, during which people’s minds were manipulated. It is difficult to reverse situations of this magnitude. Change requires widespread awareness. Some mistakes may occur, but in the end, things will be better.”

Levant24: How would you describe the years you spent in detention in terms of the overall experience?

Ragheed al-Tatari: “I would describe them as: ‘academic.’ Meaning, if one’s time in prison is used properly, the period of detention becomes an academic, or educational experience. This is time whereby the political prisoner learns from the mistakes made leading to detention, in addition to gaining experience from others and getting to know the political forces and the ideas they hold, which increases the acquisition and broadening of experience from them as well. Moreover, he can practice hobbies such as drawing, writing and reading books, thus increasing the prisoner’s knowledge.”