The cold crisp air is heavy with the shouts of vendors yelling prices, each straining to be heard over the din of other merchant. The crowded vegetable market is packed with families buying produce for the day. Abruptly the gray chill of winter explodes in a burning flash of fire and metal and the sound of yelling vendors hawking prices gives way to the screams and cries of horrified survivors and the dying. That December morning in 2013 Assad bombed a market in Aleppo, killing over of score of civilians and injuring twice as many. It was a day that would haunt Abdullah, a survivor of the attack, a decade later.

“Since 2013 I’ve been having panic attacks,” he told L24 in an interview, “ever since Assad bombed my workplace, I’m afraid of crowded places, I’ve changed jobs and locations but it hasn’t helped.” Abdullah has lived with the mental scars of that day for ten years affecting his work, family, and personal life. “My fear and depression mean I haven’t been able to get married,” he laments, “most people sympathize with me but family members have been less supportive.”

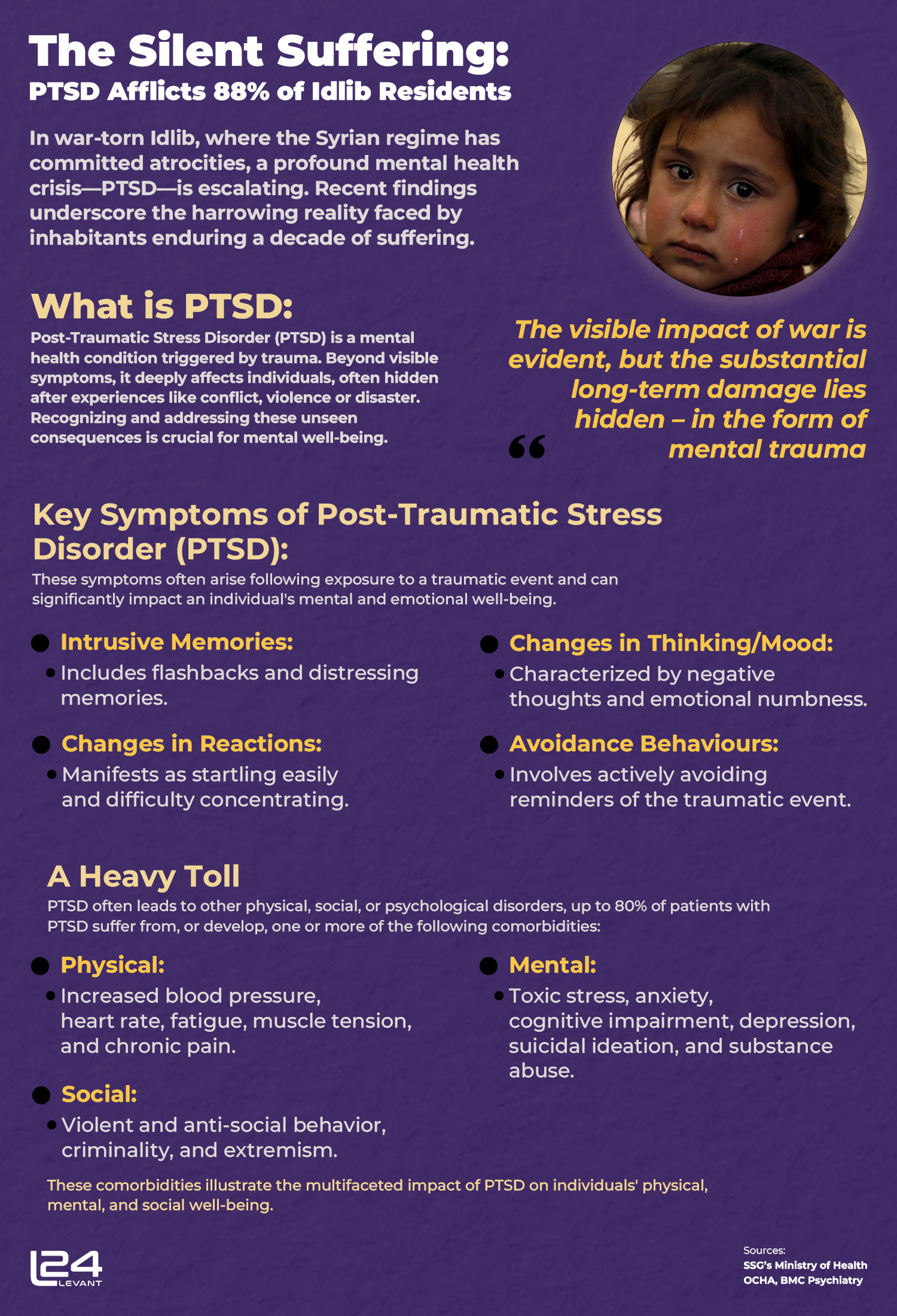

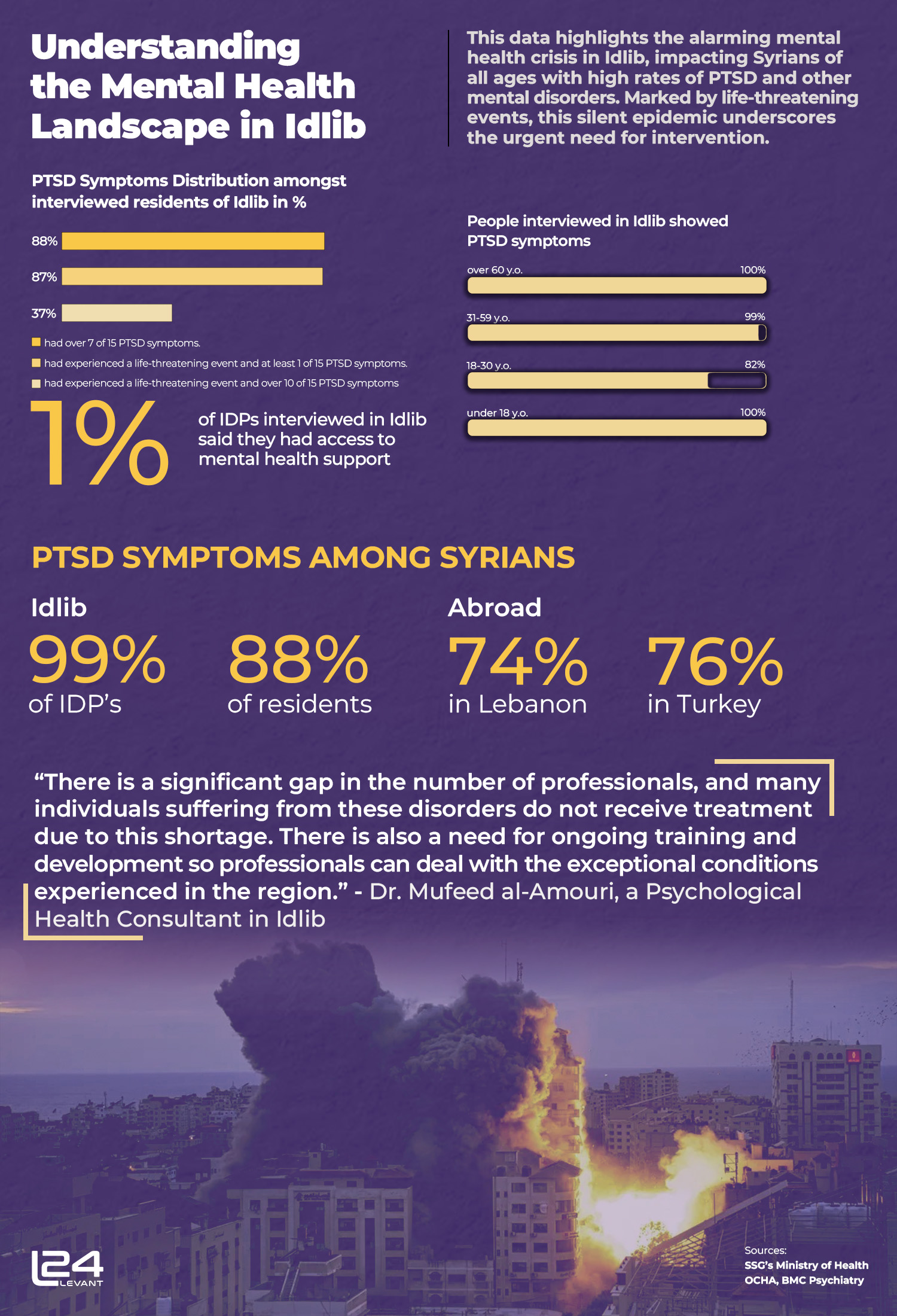

Multiple factors contribute to the urgent need for psychiatric support in northern Syria. Chief among them is the prolonged conflict and ongoing trauma experienced by Syrians significantly impacting their mental well-being. Mental health infrastructure and resources, human and material, in the region are nearly non-existent, leaving most without access to proper care. Lastly, the cultural stigma surrounding mental health perpetuates the crisis.

Unending Suffering of an Endless War

L24 spoke with Dr. Mufeed al-Amouri, a Psychological Health Consultant for the Syrian Salvation Government’s (SSG) Ministry of Health, and Muhammad Musa from Idlib, a child psychologist, regarding the dire mental health crisis in the region. Although trained to treat children, due to the paucity of psychologists and demand for treatment, Musa says he is forced to treat adults.

“The main issues,” says Musa, “are PTSD … from 13 years of non-stop war.” He identified anxiety disorders, trauma, depression, and sleep disorders among the prevalent conditions afflicting the population.

According to Amouri years of prolonged war and poor economic situation caused by displacement and harsh conditions in IDP camps have increased the suffering of many Syrians causing or exacerbating many psychological ailments. Witnessing constant violence, airstrikes, bombings, and separation from family, resultant from death, imprisonment or displacement has, says Amouri, “led to a significant increase in psychological disorders among the people.”

Her Father Murdered Before Her Eyes …

A university student in Idlib, Rehaf, told L24 about the effect seeing her father murdered had, “I lost my dad at the beginning of the war, we were walking home and a Syrian Arab Army sniper killed him, this caused a downward spiral for me,” even after years she still suffers from that day, “I have panic attacks when I hear loud noises or sounds of cars and trucks.”

Rehaf feels alienated, while her family “has moved on” she has been unable to, “Only my brother has supported and listened to me,” the only one that speaks to her about her “depression and fears,” she says the rest of her family believe she should “get over it.”

“It has really affected me,” says Rehaf, “I don’t go out and I only have one friend.” She recognizes the trauma she goes through is societal, “anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, it’s real and we (Syrians) all suffer from it on some level.”

According to a study by Dr. Amy L. Drapalski, stigma plays a significant role in the lives of individuals with PTSD, particularly when considering the influence of cultural and societal pressures. Cultural factors, such as societal expectations and norms, can further exacerbate the stigma surrounding mental illness. Some cultural and societal pressures can contribute to the internalization of stigmatizing beliefs, causing feelings of shame, isolation, and reluctance to seek treatment.

I Lost Everything in an Instant…

Ayah, who lost her husband and children, told L24, “I was happily married with two children, then a Russian airstrike in a busy market changed everything. Both my sons and husband were killed instantly, everything changed that day… I can’t forget it.”

Acknowledging psychological issues are considered taboo by many Syrians, this is because, according to Drapalski, in certain cultures, seeking help for mental health issues may be seen as a sign of weakness, defect, or deviation from traditional gender roles. “People aren’t supportive, because they know I go to therapy with my father,” Ayah asserts, “the treatment I’m getting is only because my father begged me to.”

No Doctors in a Sea of Sick

The deficit of qualified mental health providers is one of the primary challenges facing the liberated territories, “the number of professionals on the ground is insufficient to meet the demand,” Dr. Amouri explains, “There’s a significant gap in the number of professionals, and many individuals suffering from these disorders do not receive treatment due to this shortage. There is also a need for ongoing training and development so professionals can deal with the exceptional conditions experienced in the region.”

An absence of trained professionals and facilities, especially for women, in a culture wherein gender-based care is normative places further difficulties on those seeking help, as Ayah explains, “It’s hard to open up, especially for a woman. We need more clinics and female psychologists.”

Musa agrees, saying cultural aversion and scarcity of human resources are a problem, “My practice at the moment is overwhelmed, I’m at full capacity with no support, there’s a huge demand for psychologists and mental health clinics – and this bear in mind is a taboo subject in this part of the world. In terms of cultural and educational barriers, it’s about the same, for example, there are no child psychologists in my vicinity and I have 76 young people currently receiving help and support.”

The Future at Risk

If unaddressed the mental health crisis, especially that of PTSD, like most health issues, will not vanish by leaving it untreated, it is, in fact, likely to worsen. When left, PTSD often leads to other serious issues such as marital and interpersonal relationship problems, domestic abuse, substance abuse, self-harm, harming others, and suicide. According to a 2021 report by UNHCR, over 3.7 million Syrian children and adolescents were deemed to require treatment for PTSD and related psychological ailments. In the time since, the numbers are only likely to have grown, endangering the futures of nearly four million Syrians – an entire generation.

Syrian children are most at risk of permanent long-term damage due to the mental health climate as Harvard Child Protection and Mental Health Specialist, Alexandra Chen Ph.D. mentions, “Daily exposure to the kind of traumatic events that Syria’s children endure… will likely lead to a rise in long-term mental health disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), overanxious disorder (OAD) – and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the conflict ends.”

Among the greatest threat to children, which Dr. Chen mentions, is toxic stress, which is the “most dangerous form of stress response,” according to her it can greatly impair physical, cognitive, and socioemotional development and “have a life-long impact on children’s mental and physical health.” This toxicity, says Chen, is caused by stressful environments such as war zones and puts millions of children at risk of serious physical developmental disorders which can damage the brain, hormonal systems, and other organs, while increasing the likelihood of lasting cognitive impairment and diseases like; heart disease, diabetes, and immunodeficiency, as well as social issues such as substance abuse, depression, and other psychological disorders into adulthood.

A report by Save the Children (STC) mentioned the far-reaching impact of the mental health crisis in Syria, especially to the children, “The risk of multigenerational trauma, where the untreated effect of the crisis on today’s young people is passed on to their own children and future generations, grows more serious every moment the war goes on. We have seen in other conflict situations how higher levels of drug and alcohol abuse, depression, suicide, domestic abuse, and extremism are present in communities years down the line.”

While Dr. Chen makes clear there is hope in treatment she warns that time is essential to ensuring that damage is not long-lasting or even permanent, “if children have supportive relationships with caring adults early in their lives, the damaging and potentially deadly effects of toxic stress can be reversed … however, many of Syria’s children have lost much critical time for development, and the long-term damage has the potential to become irreversible and permanent.” STC also sounds the alarm highlighting the urgency of the situation, “millions of children have been so consistently exposed to toxic stress that their chances of recovering fully are dwindling by the day.”

A Way Forward

“There are 4.5 million people in the liberated areas and most, if not all, have suffered and witnessed horrific tragedies and events,” comments Musa on the severity of the situation, “what we need,” he posits, “are professional male and female psychologists.” Which, according to Musa, would mean ensuring that educational and training programs in the discipline are implemented to meet vital societal needs, “Education in the field of psychiatry is almost unheard of,” he states, “but there are signs of young students showing interest in this field and courses will be available at Idlib University.”

Amouri adds, “Training in psychology was mainly conducted by local and international humanitarian organizations and was limited only to specific demographics (women, children, orphans)” The absence of a humanitarian mechanism decoupled from Assad, Russia, and their ongoing political interference results in vital programs canceled, stopped for long periods, or experiencing inadequate funding or staff. However, without external assistance Syrians have taken the initiative, “There are now colleges and institutes for counseling psychology,” says Amouri, “and they’ve started training and preparing professionals, but they’ve yet to enter the field.”

This is why funding for both external and internal programs is key to addressing this crisis, it is crucial to increase funding for mental health programs by NGOs like Syria Relief, the Union of Relief and Development Associations (URDA), and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UMCRO), a humanitarian NGO working in northern Syria. These organizations play a vital role in providing social-psychological support and holistic protection interventions for IDPs, refugees, and conflict victims.

This crisis in Syria is a pressing issue requiring immediate attention and global intervention. The prevalence of psychological disorders, coupled with a dearth of resources and stigma surrounding mental health, pose significant challenges to the well-being and stability of the population. By addressing these issues and providing comprehensive support, it is hoped such efforts can contribute to the overall recovery and resilience of the Syrian people, helping to safeguard their future.