The Syrian regime, under the leadership of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, has been accused of perpetrating crimes against humanity and severe persecution against the Sunni Muslim population. Yet while there are those who have testified to their experiences under the Assad regime there remain detractors who point out that Sunnis alongside, Christians, Druze, and Alawites are among the regime’s supporters and even take part in the military, parliament, and governance. To fully understand the context of such claims one must examine the history of Syria and the Assad family’s rule.

Myth of the Persecuted Majority?

Many have said that the Sunnis in Syria were not persecuted; after all, they comprise nearly 80% of the population and hold positions of influence in business and the government. However, a report on religious freedom in Syria by the US Department of State indicated that in terms of the Assad regime’s human rights abuses against its perceived opponents, the majority were Sunni Muslims. The report noted that most individuals killed in regime custody were Sunni Muslims, targeted for their perceived opposition or likelihood to support the opposition.

The report also mentioned the presence of Sunni, Christian, Druze, and Kurdish members in parliament, but highlighted that the body did not function independently and was subject to the control of the head of the regime (Assad). Emphasizing that the Alawite minority held greater political power in the cabinet and leadership positions in the military, security, and intelligence services, with religion remaining a factor in determining career advancement within the government.

Furthermore, a 2020 report by the EU Agency for Asylum noted that Alawites held key regime positions, dominated the police and the army, and had high-ranking positions in elite military and militia units. The report also highlighted the higher chances of Alawites obtaining employment in the public sector compared to other groups such as Christians, Sunni Arabs, or Kurds. While a majority, the publication showed Sunnis were underrepresented in positions of power and influence and were the victims of most abductions, arrests, restrictions, and extrajudicial killings. Yet how did this come to be?

Hafez Assad the Father of the Police State

Historian Kamal Abdo, who holds a PhD in modern history, spoke with L24 about the founding of the current Syrian system. According to Abdo, it began as a colonial-French presidential-parliamentary system before undergoing various changes eventually culminating in the concentration of power in the hands of the Baath Party and the military committee. This in turn led to Hafez Assad’s seizure of power in 1970 and the transformation of the governance system into a centralized individual system centered on the presidency.

“The Alawite ascent to power did not happen abruptly with Hafez Assad’s 1970 coup,” Abdo explains, “it began with military coups starting in 1949. With each coup, Sunni officers permanently left the country.” He continues explaining that during the UAR period when Egypt and Syria were under the leadership of Gamal Abdel Nasser, “Nasser contributed to dismissing hundreds of Sunni officers, branding them as reactionary and Baathist agents. The expulsion of Sunnis intensified with the Baathist coup in 1963, culminating in the complete control of the Baathist military committee, clearing the way for Hafez Assad’s takeover.”

Once he solidified his power Hafez set to work ensuring he would not be victim to any coups or plots by building a security apparatus and country where even “the walls have ears.” Sheikh Dr. Anas Ayrout, of Idlib University, spoke about life under the police state of Hafez, “the Sunni community, especially in matters of religion, religious lessons, and sermons, was suppressed. Security branches controlled religious affairs, and religious endowments were merely an office within the security branch.”

Hafez created a system whose policies extended to education, military service, and all aspects of public life, creating a pervasive atmosphere of fear and oppression for Sunnis. Preachers, teachers, and students were often called in for questioning; religious gatherings were closely monitored or forbidden, often resulting in interrogations. Travel abroad needed clearance from the intelligence and even then, there were often members of the security services monitoring expatriates overseas.

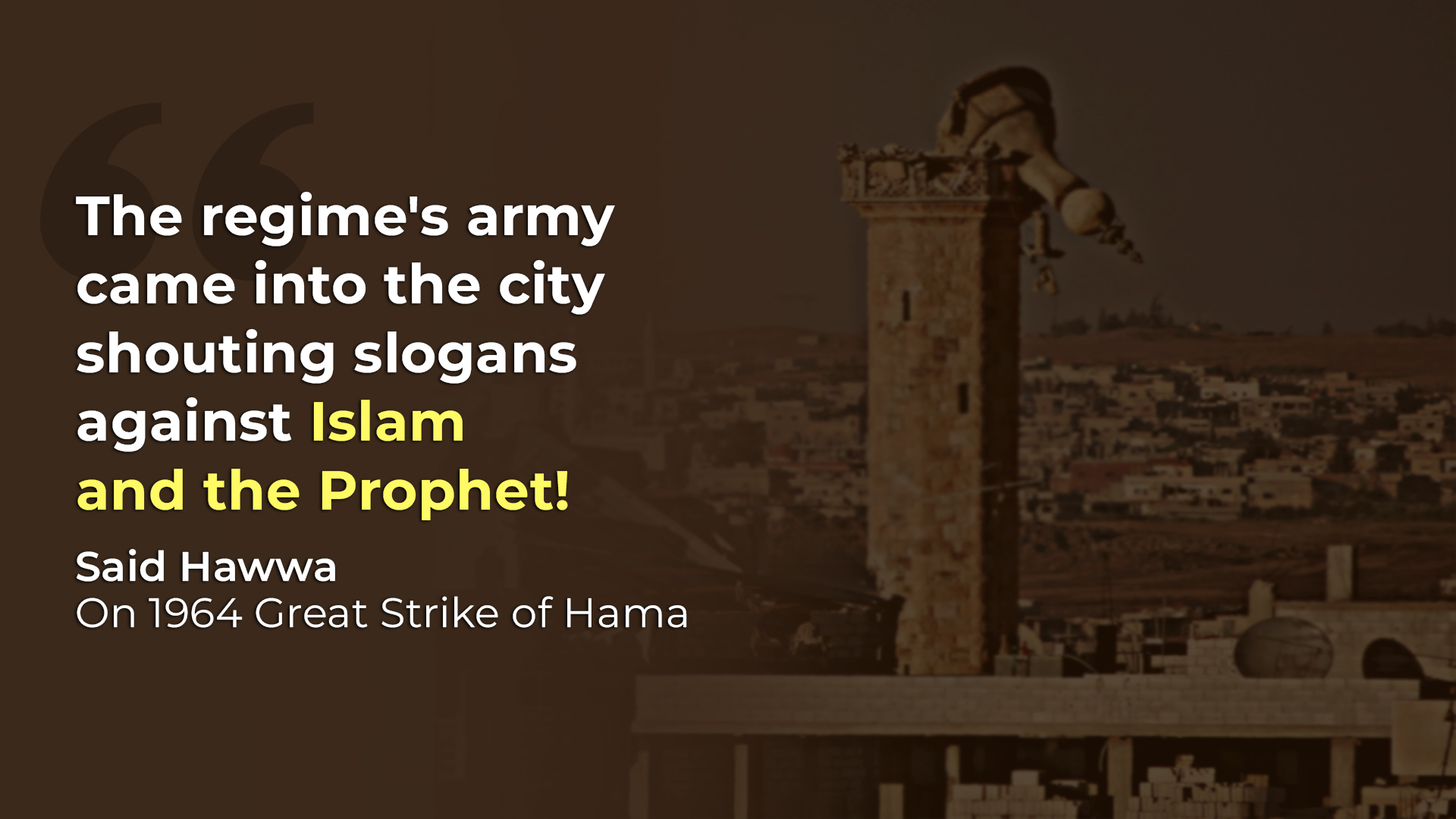

However, the state did not limit its actions simply to surveillance, restrictions, and arrests, “The regime,” says Ayrout, “had a history of criminality, bloodshed, and violation of sanctities in the massacres of Hama and Jisr al-Shughour in the ’80s.”

According to Abdo, “Sectarian discrimination and the spread of sectarianism throughout the state were the main reasons for the armed Sunni uprisings in Hama in 1964 and later the events of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s, during which the regime committed the infamous Hama massacre, killing over 40,000 Sunni residents of Hama, in addition to other massacres in Aleppo and Idlib.”

Hafez ruled Syria with an iron fist for nearly 30 years before passing away in 2000 and leaving the throne to his son Bashar. Some were hopeful that under the London-educated doctor, things may be different.

A Dynastic Cult of State

“Bashar followed his father’s system, not inventing anything new but mastering the game his father had created,” Wael Alwan, an analyst for Jusoor Studies, told L24. “Despite the regime’s brutality and corruption, Bashar excelled in the political game, both internally and externally.” Those who thought that perhaps Syria would face a new era of democracy and freedom quickly realized that Bashar would not only continue the decades-long system of oppression and tyranny but would exceed his father in brutality and persecution and would spark the Syrian revolution.

While many see the Assad regime as the sectarian rule of an Alawite minority, Alwan argues against what he calls “the exaggeration of religious and sectarian divisions,” instead attributing those to the regime’s deliberate actions. He emphasizes the regime’s reliance on loyalty to itself and its system, rather than simple sectarian affiliations, and notes its distribution of power and wealth based on allegiance to the regime – the Assad family.

Alwan points out those key figures in the history of the regime, such as Mustafa Tlass, a Sunni, were from different sects but remained loyal to the regime’s system of oppression and corruption. He also discusses how the regime established its structure based on devotion, with the religion of officials being the worship of the regime, and the doctrine of its loyalists being the sanctification of the regime and Assad family.

Key to this cult posits Alwan is the strategic distribution of power and wealth, and individuals from various regions are part of this balance, with reward based on allegiance rather than sect, ethnicity, or locality. However, this view does not conflict with the reality of Sunni persecution nor evidence of Alawite ascendancy but merely re-contextualizes the motivations behind the actions of the cult of the state. “Dictatorships,” Alwan explains, “rule by asserting themselves as the supreme authority.” It is important to note that this is an ideology in direct conflict with the fundamental principle of Islam (Tawheed) which places God as the only supreme authority, and one of the reasons the regime held such hostility toward the religion.

Assad Regime’s Animosity towards Islam

This is at the heart of the hostility that the regime of the Assad family has with the Muslims in Syria. Their system cannot accept anything above it and considers any people who have loyalty to anything before the state and regime as a threat.

In Spiritual Humiliation: Sectarian Torture Tactics in Assad’s Prisons, Malak Shalabi details the systematic targeting of Sunni Muslims and their religious beliefs in particular, by the Assad regime’s security services. The study documents the systemic attacks on Islam and its core beliefs chief of which is the monotheist concept of Tawheed (the idea that nothing is worshiped, obeyed, or supplicated to except for Allah).

Shalabi notes that members of the security forces habitually curse God, and the prophets, forcing prisoners, including children, to prostrate to pictures of Bashar, to declare Bashar as their god, to pray to him and systematically force prisoners to commit and engage in actions of blasphemy under duress using physical, sexual and psychological torture.

She shares the story of Abdullah who said, “We prayed at home because going to the (mosque) would be dangerous, (our) family’s friend, who would take his sons to the (mosque) for dawn prayer was detained for two years for that.” While attending dawn prayers is common throughout Muslim countries, and held by some Islamic jurists to be obligatory upon males, the government considers it a sign of people who take Islam seriously, and hence a threat.

Dr. Yasin Aloush, Dean of the Faculty of Sharia at Idlib University, said about life under the regime, “There was no religious freedom in its true sense. It is known that security branches pursued and monitored religious individuals. In one of the security branches liberated from the regime, revolutionaries found lists of the names of those who regularly attended dawn prayers in mosques in Idlib and its countryside.”

Attacks and restrictions on the practice of Islam were not restricted only to the prisoner as Ayrout mentions, “The regime encouraged corruption, propagated indecency, and allowed the opening of places involved in various illicit activities. It also prohibited the wearing of the hijab in schools, and forced men and women to intermingle.” He noted that just as in the dungeons of the intelligence, during “compulsory military service, Sunnis were targeted for their beliefs, with insults and mockery directed at their religion and Islamic rituals. Syria became a prison for Sunnis in every sense of the word.”

Freedom a Fruit of the Revolution

Despite the Assad regime still clinging to its throne in Damascus many territories have been liberated, allowing the former oppressed Sunnis to experience an Islamic revival and real religious freedom for the first time in 50 years. “There is a sense of freedom,” Abdo, reflects, “the reclamation of values, and cultural and religious heritage that the regime diligently worked to obscure and erase for decades. … It is a rare case in the history of this region for a nation to govern itself, as is happening today. While the situation is not as desired, it is certainly much better than before. The challenges and economic hardships represent a necessary toll that people must pay to gain their freedom from regimes accustomed to oppressing and marginalizing them. True, the virtuous city may still be distant, but the journey toward it is worthwhile.”