L24 conducted an interview with seismologist Dr. Chris Milliner a geology research associate at Caltech to get a more in-depth understanding of the science behind earthquakes in hopes of understanding the event which occurred on February 6th in southern Turkey and northern Syria.

L24: How powerful was the seismic event which occurred in Turkey February 6th and was it one or multiple earthquakes?

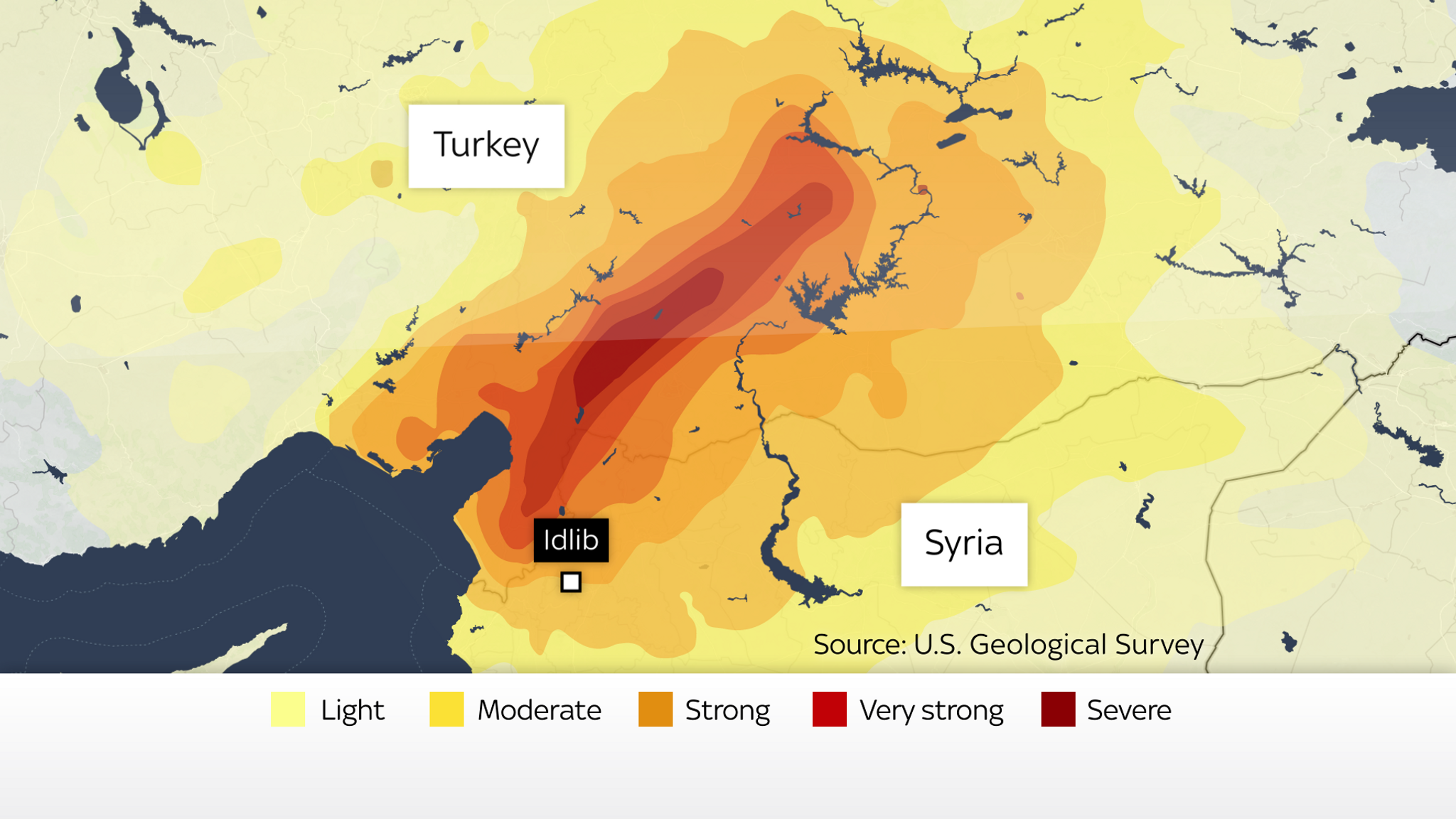

Dr. Milliner: The recent earthquakes in Turkey were significant and involved two separate earthquakes that occurred along different parts of the East Anatolia Fault system. First there was the Mw 7.8 which occurred along the main part of the East Anatolia Fault, then about 9 hours later the Mw 7.5 occurred on an offshoot part of the East Anatolian Fault. The Mw 7.8 released more than twice the amount of energy than the Mw 7.5 earthquake and was the largest earthquake in Turkey since the 1939 Mw 7.8 Erzincan event. The two recent earthquakes are likely related, but it’s not clear exactly how the large Mw 7.8 earthquake triggered the Mw 7.5.

L24: What is the difference between an earthquake and an aftershock? And can aftershocks be as powerful or more powerful than an earthquake?

Dr. Milliner: An aftershock is also a regular earthquake but we call it that when it occurs after a seismic event that is larger in magnitude (the mainshock) and is within proximity to the mainshock, specifically within the distance of one fault length from the mainshock. If another, more recent earthquake occurs that is larger than the previous one, then we change the names and the new, larger earthquake is defined as the mainshock and the first and smaller earthquake would be called a foreshock. In this case the Mw 7.8 is called the mainshock and the Mw 7.5 is the aftershock.

L24: Even five days after the initial event aftershocks continue to be felt both in Turkey and Syria how long do aftershocks typically last?

Dr. Milliner: The number of aftershocks tend to decay approximately exponentially with time after the mainshock, this behavior is well known in earthquake science and is called Omori’s law. There are typically many aftershocks immediately after the mainshock and then there are gradually fewer. For example, after 10 days there will be approximately 10 times fewer aftershocks than since the first day and after 100 days, ~100 fewer times the number of aftershocks. Although we have a general understanding of how the number of aftershocks diminishes with time, we don’t know exactly how the magnitude of events changes with time.

The duration that aftershocks last depends on how large the mainshock is. Felt aftershocks can last weeks-months or beyond, and they are more common in the region near and surrounding the mainshocks and other large aftershocks. However, we cannot yet predict earthquakes, there is no science behind such claims, we can only calculate the probability of one occurring. Aside from the many earthquake science experts in Turkey, another good resource to find information on aftershocks is the United States Geological Survey (the USGS).

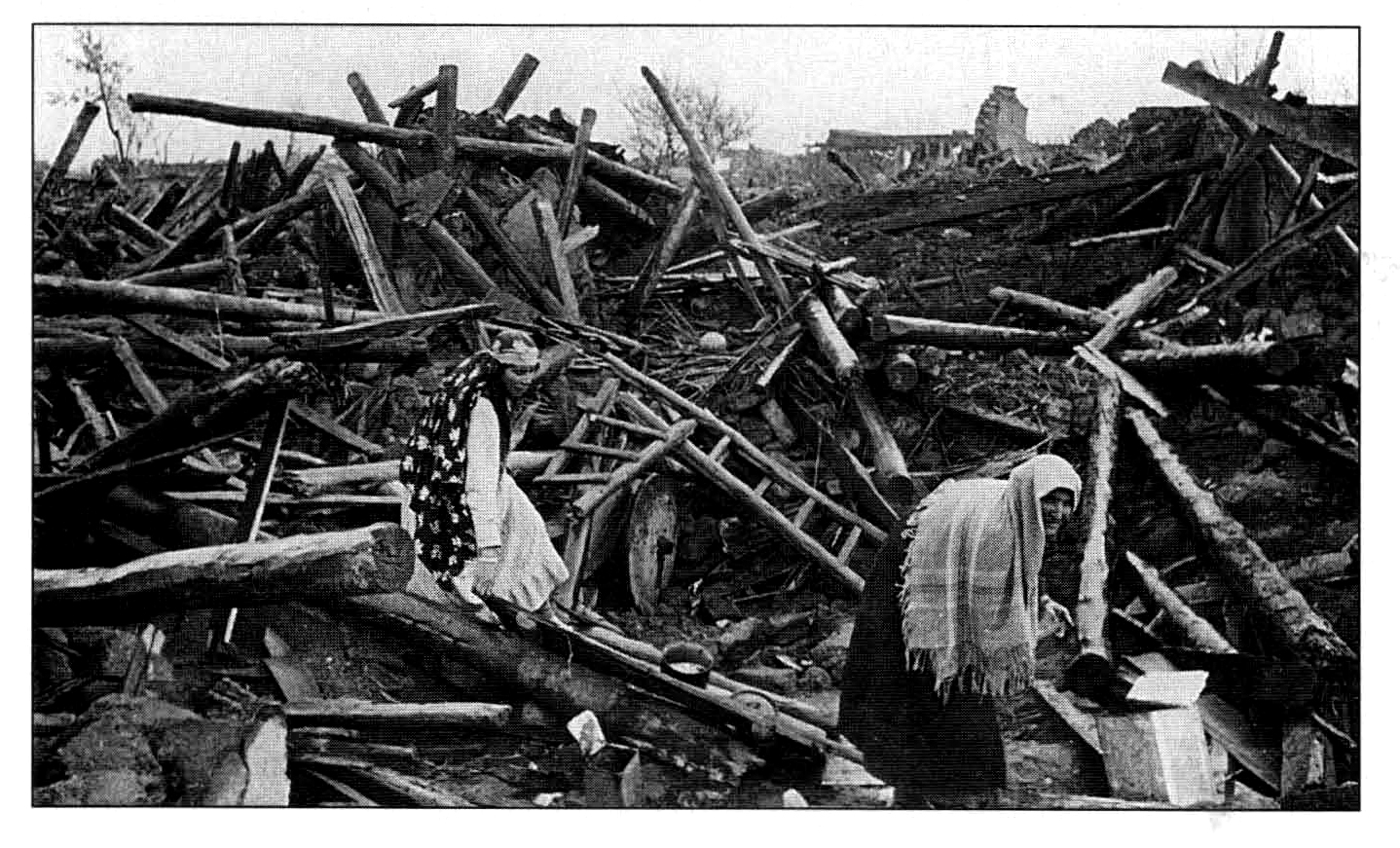

Dr. Milliner: The tragedy that unfolded this past week was horrific; there are a number of reasons why it was so deadly. The large size of the earthquake is one such reason. The Mw 7.8 earthquake ruptured a fault over a 300 km distance, which led to significant ground shaking over a very large area. Second, the proximity of many urban areas to the faults that ruptured during the earthquakes is another, as that is where ground shaking is usually largest.

In addition, the low temperatures in the region have not helped in terms of survivability for those trapped under rubble. Last but not least, is the poor building construction. In this case, many lives were lost because building codes were not followed or enforced. A common phrase that is used is that “earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do,” and that there are no “natural disasters”, but natural event that overlaps with a vulnerable system. Hopefully, this will be a moment for actual change in how buildings are constructed and enforced.

L24: Historically, when compared with previous events throughout the world, how does what we are seeing today rank, in terms of these previous disasters?

Dr. Milliner: I don’t feel comfortable answering this question. By no means, this event was significant in its loss of life and hopefully it will be a moment for real change in how buildings are constructed in Turkey and Syria. However, I don’t think there is a lot to be learned in terms of ranking disasters and the number of people who are no longer with us against previous ones.

L24: What are the greatest dangers presented by these types of events?

Dr. Milliner: The greatest danger of these types of events are strong ground shaking which can cause building collapse and the fault motion which can rupture through critical infrastructure like gas, electricity water pipelines and telecommunication lines. Then there are the secondary effects that result from the earthquake such as landslides and liquefaction, where the latter results from saturated sediments which can destabilize the foundations of buildings. Lastly, there are tertiary effects such as outbreaks of disease, starvation and access to clean drinking water. This is why continued aid to the region is important well after the earthquake has stopped as critical lifelines may be incapacitated for some time.

Dr. Milliner: Earthquakes cannot be predicted. There is no scientific backing to such claims. Similar to how we can’t predict what the weather will be exactly on a certain day we can’t say exactly how large an earthquake will be on a certain day or place.

However, we can measure where the crust is being strained and where the faults are located. This tells us where tectonic energy is accumulating that will be released in an earthquake. Although we don’t know when earthquakes will occur, we can measure where they are more and less likely to occur. The region along the East Anatolian Fault has been known to accumulate tectonic strain and there is known evidence of past earthquakes on the fault systems, and therefore is a region with high seismic hazard.

L24: How likely is it that another event of this magnitude will occur again, regionally or globally and what can be done to better prepare for such disasters?

Dr. Milliner: We cannot predict whether another event of this magnitude will occur again. There is no science behind any prediction of earthquakes. However, what we can say is whether a region has a higher or lower likelihood of an earthquake over some period of time (usually over a 30-year period, which is a time-frame relevant to building construction).

To prepare for another possible earthquake, it is best to be as prepared as you can. One way is to make an earthquake kit. This includes having emergency food, water and medical supplies. You can find information here. Second, you should make an emergency plan, including people you can contact and stay within a different region as well as which possible routes you can take. Third secure your home against heavy things that could fall over such as refrigerators, bookcases, water heaters and TV’s or anything that hangs on a wall. If you feel shaking then remember to duck, cover and hold-on.