The first burst of gunfire lit the windows of western Aleppo in a frantic staccato. Residents later recalled how the sky glowed orange above the apartment blocks while smoke drifted across empty streets. On one of those nights, a sleeper agent received a call from Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, then commander of the Repelling the Aggression Operation.

Despite the chaos around him, the voice on the other end stayed calm. “Head to so-and-so and convey my message,” Syria’s future post-Assad President instructed, according to a senior official familiar with the matter. The road ahead was a corridor of flames. “Ready? We are going in,” the man whispered to his companion before stepping into the darkness of a historic night reverberating with the echo of artillery.

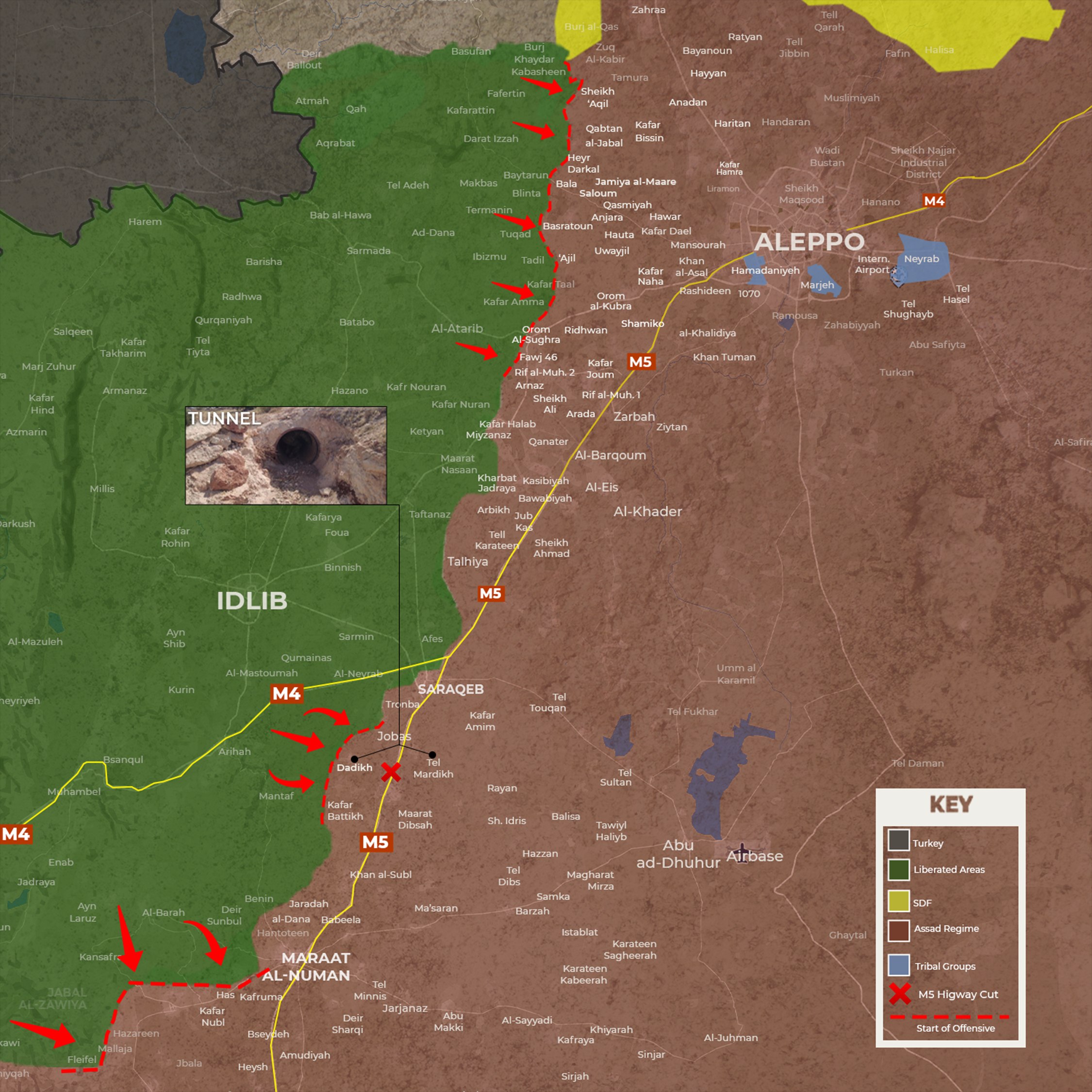

Scenes like this marked the beginning of an 11-day campaign that reshaped Syria’s front lines. The Fath al-Mubeen Operations Room (FMOR) had spent years preparing for confrontation with the Assad regime. Its commanders described the period as one of defensive entrenchment, restructuring, and training that gradually shifted toward coordinated offensive pressure in a series of special operations as the Assad regime’s positions thinned. Revolutionary units dug in across Idlib’s fields, repositioned artillery, expanded drone capabilities, and worked quietly with allied tribal groups in northern Aleppo and western Idlib.

Three battles greatly facilitated Syria’s liberation. The surprise attacks in Aleppo City as revolutionary forces approached from the west, the tunnel maneuver in Dadikh, and the fall of Zain al-Abidin, the regime’s fortified mountain in Hama. These strategic victories helped shape the flow of the remaining battles, culminating in the December 8 victory of the Revolution and the 2024 fall of the Assad regime.

Infiltrating Aleppo on the Road to Liberation

Leading up to the offensive, FMOR quietly reorganized its elite formations under the Command of Military Operations (CMO). This umbrella force would become the central structure behind the later push across the northern and central provinces. The commanders saw Aleppo as the decisive target, calling it “the ultimate prize” in internal planning documents. Months of surveillance identified the heart of the regime’s command network, a joint operations room used by Russian, Iranian, and Syrian officers inside Division 30.

To strike that node, planners turned to the Red Bands, a special forces unit trained to operate behind enemy lines. The team infiltrated the city after operatives purchased access with bribes and secured passage through a private vehicle. Fighters already hidden inside Aleppo guided them through checkpoints. They wore uniforms modeled on the regime’s uniforms and even used a style of vehicle favored by officers to avoid suspicion.

Upon reaching the gate of the operations center, the men blasted music and staged an argument to pass as quarrelsome guards waiting for an officer. They dispersed across the barracks before dawn. According to internal accounts compiled after the attack, the assassinations began during a meeting that brought together regime and Iranian officers. The fighters then held their positions until they were killed. The operation paralyzed field command for the Aleppo axis and created what one officer later described as a psychological rupture in the city’s defenses.

The collapse that followed opened corridors for CMO units pressing from western Aleppo. Arab tribal groups positioned in districts around Hamdaniya and Marja coordinated with the advancing forces, facilitating safe transit inside several neighborhoods. As the regime’s lines buckled, sleeper cells embedded earlier through contacts between Hajj Khalid al-Marai of the Baqir Brigade and Jolani were activated in Marja, Nayrab and other areas. Local sources reported Marai had previously not divulged his role in the operations due to security concerns.

‘Falcons’ Take Flight…

Another component of the preparation was the Shaheen Brigades and their growing drone program, taking their name “Shaheen” from the Arabic name for the peregrine falcon. Production began in 2016 and moved through several development phases, relying on a mix of domestic work and external parts.

By 2017, the drones were changing battlefields across northern Syria. Surveillance models provided real-time intelligence day and night, using thermal and night-vision systems that fed directly into FMOR and CMO planning. In the months before the Repelling the Aggression Operation, these aircraft mapped regime trenches, tracked vehicle movements, and helped shape the order of battle.

Combat models soon followed. Shaheen crews targeted communications networks and command posts in the western countryside of Aleppo and Hama’s Zain al-Abidin Mountain. Several strikes disabled 23mm anti-aircraft guns and destroyed armored vehicles. The program fielded everything from quadcopters to fixed-wing aircraft, with variants built for reconnaissance, “suicide” missions, and precision munitions delivery. Fighters described the psychological impact as almost equal to the material effect. The drones unnerved regime forces while giving revolutionary units a sense of growing control over the sky.

The Tunnel of Tel Mardikh

While Aleppo loomed large in the public eye, and Shaheen drones prowled the skies, another no less important operation was ongoing under the radar, beneath the earth of Idlib. At Dadikh, FMOR forces and allied engineering crews spent half a year digging, widening, and repairing an old drainage tunnel that stretched toward Tel Mardikh. Final work and repairs continued almost without pause for two months, during which two special forces members suffocated during the excavation due to malfunctioning equipment.

Abu Jabir, a member of the Red Bands, explained why the tunnel became the chosen route. “The challenges were the obstacles present in the terrain and the military obstacles that the regime had improved,” Jabir told Levant24. He said the planning lasted six or seven months while the assault itself unfolded in just under an hour.

The importance of the operation, say the fighters, was to create a diversion, confuse regime forces on the front, and disrupt logistical access along the vital M5, through which reinforcements could be sent to Aleppo from the South via Hama.

“The success rate of the mission was thanks to God Almighty. It was an unexpected success,” he said. He recalled a moment when the oxygen inside the tunnel dropped during reconnaissance, leaving two men struggling to breathe. “One of the biggest challenges for me and the brothers who were present in this operation was simply moving through the tunnel,” he said.

Only part of the force managed to cross because the compact motorized vehicle used for transport was immobilized. The group fought through regime positions from behind, using the advantage of surprise. CMO forces then crossed the mined front line with heavy weapons and pushed toward Dadikh and Kafr Batikh. While none of the infiltrators were killed in the initial assault, several fighters died when regime forces shelled the area west of Dadikh.

The Floodgates are Opened…

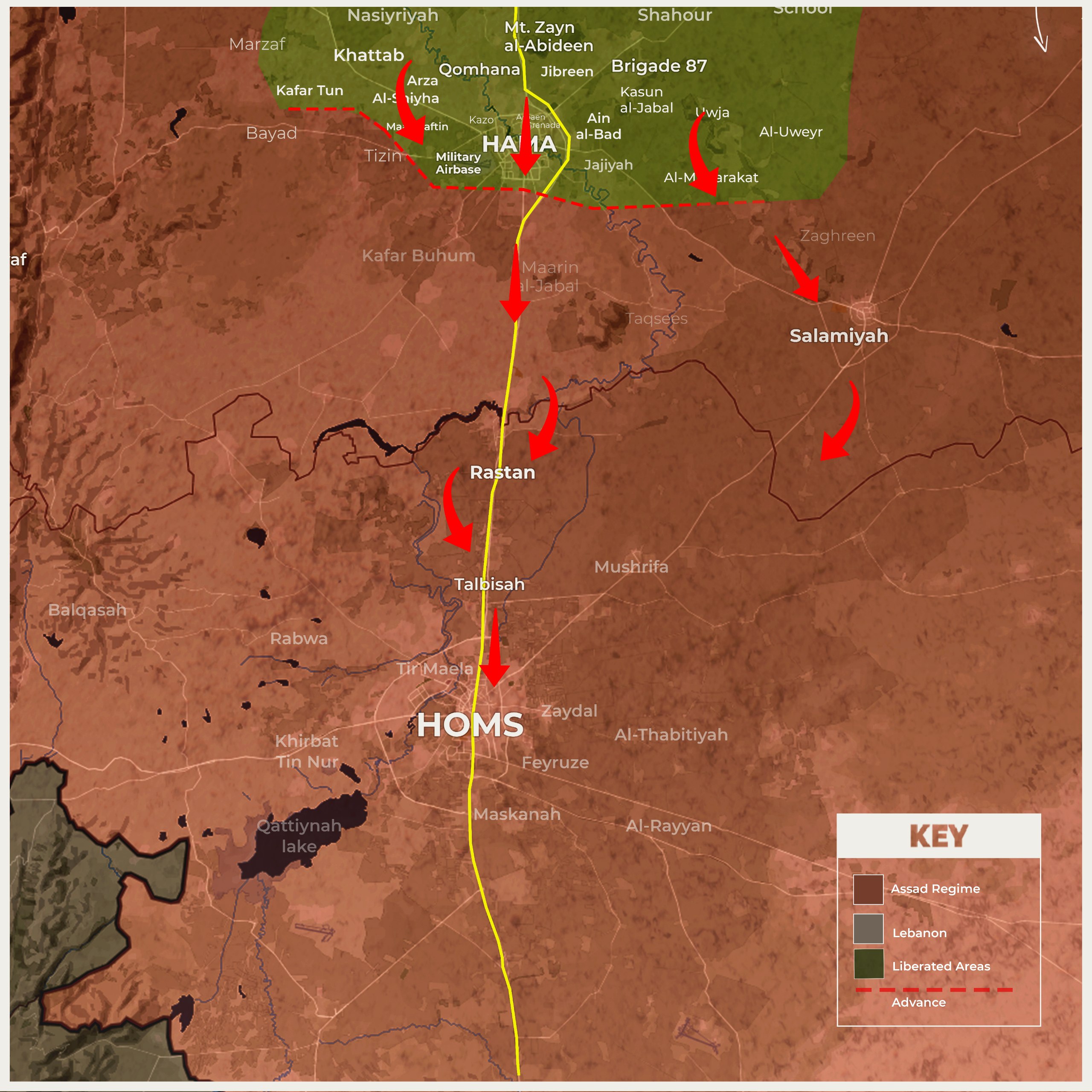

As Aleppo and Idlib shifted out of Assad’s hands, CMO units began a steady move toward Maraat Numan, Khan Sheikhoun and Abu Dhuhur, then pushed farther east toward Khanasir and Safira. By the time the northern front stabilized, CMO troops were already entering Hama province.

Zain al-Abideen Mountain had long been considered one of the most fortified positions in central Syria. Earlier attempts to capture it had failed as Assad defended it as a strategic anchor for Hama and the central corridor. Russian aircraft and Iranian-aligned militias, including Hezbollah and other sectarian units, reinforced the position and treated it as a line that could not fall. From its peak, radar, communications stations and surveillance posts monitored movements across the province. Regime commanders relied on the mountain to secure Hama, supply routes to coastal strongholds and the operations of the infamous “Tiger Forces” stationed nearby.

The battle for Zain al-Abidin Mountain became a test of endurance. The high ground overlooked large stretches of Hama and held radar stations, air defense systems, and a vast weapons cache. Regime forces dug in and resisted for days. When the advance stalled, CMO deployed the Red Bands. They marched nearly 12 kilometers overnight under constant fire, reaching the mountain’s edge just before dawn.

Ahmad al-Farusi, a trainer in the Red Bands, told L24 the decision to strike the mountain was unusually urgent. Normally, operations required months of field study, but Aleppo’s sudden collapse forced commanders to move without delay. Fighters memorized the route, planned contingencies, and stepped off within a day of receiving the order.

Regime gaps in experience of night surveillance and operations and poor thermal coverage created openings the Red Bands could exploit, said Farusi. Some men, he recalled, said they passed within meters of regime groups without being detected, moving slowly enough that not a single pebble slid beneath their boots.

According to internal battle notes collected after the engagement, the fighters wore uniforms altered to resemble the enemy and briefly tricked a regime unit into approaching them before eliminating the patrol. After hours of clashes, they forced surviving troops to retreat toward Hama city, where a flanking force intercepted them. The fall of the mountain allowed revolutionary forces to isolate Hama’s outlying countryside and suburbs and contributed to the seizure of the Hama Military Airport.

For those who fought there, the fall of the mountain was more than symbolic. Farusi called it the key to Hama’s liberation, arguing that no advance into the province was possible while artillery, missiles, and surveillance systems remained above them. Once the summit was taken and its communication towers disabled, regime units lost coordination. Special forces detachments withdrew or fragmented, and the road into Hama opened in hours rather than days.

The Road South: Diplomacy, Negotiations and ‘Sleeper Cells’

From Hama, the front spilled toward Homs. Russian aircraft bombed the Rastan bridge in an effort to halt the advance. By that stage, political contacts between the revolution’s leadership in Idlib and Russian intermediaries were already underway to limit further confrontation. It became clear to Moscow that Assad was a lost cause, rather than risk losing everything remaining of their Syrian presence it was best not to continue military action.

Hezbollah units began withdrawing toward Lebanon as CMO broke through the remaining pockets. In the south, local factions and sleeper cells in Daraa and Suwayda coordinated uprisings that cleared regime positions.

These units moved north toward Damascus while the main CMO columns advanced from Homs and the central corridor. Resistance collapsed through force or negotiated surrender until fighters from both directions converged on the capital.

While Russia was contacted through intermediaries negotiating battlefield limits, the Political Affairs Department of the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) clearly indicated to regional governments that revolutionary forces sought no confrontation with foreign states.

Officials reiterated that the conflict was a Syrian matter and urged outside powers to avoid deepening their involvement. The effort aimed to prevent escalation at a moment when regime lines were collapsing, and militias from Iraq, Iran, and Lebanon were reassessing their positions.

Following the victories in Aleppo, Hama, and Idlib countrysides, Homs, Suwayda, Daraa then Damascus and its suburbs were all liberated in rapid succession. By the end of the 11-day campaign, revolutionary forces had extended control across every province, including eastern units deployed toward Deir Ezzor. Commanders described the period as the most decisive chapter of the conflict, one won not by political deals but built on years of preparation and hard fought battles in tunnels, mountains, and alleys.

A tribal fighter remembers the liberation of Aleppo as one with a mix of tension and pride. “It was a night written in memory,” he recalled. For the forces that followed him, it marked the beginning of a chain of events that would redraw the map of Syria and would be scrawled within the annals of history.