“There are mass defections among Arabs,” the man said quietly, choosing his words with care. “Abdullah” had already defected, leaving the front lines behind, yet asked that his name not be published, as members of his family remain in Raqqa. A single post, a single quote too clearly attributed, could cost them their livelihoods, or worse. “There is a media blackout… because they are treated in the same way people were under the Assad regime,” he said, explaining why few speak openly.

His account points to a deeper struggle unfolding inside the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), one that rarely appears in official statements or diplomatic readouts. Behind the language of unity and negotiation lies a set of unresolved tensions over identity, authority, and the future of northeastern Syria.

At the heart of it is a fundamental divide between those pushing for reintegration into the Syrian state and those remaining committed to an ideological project rooted in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the teachings of its founder, Abdullah Öcalan.

Competing Visions Behind a Unified Front

Publicly, officials affiliated with the SDF and its political umbrella emphasize cohesion. Abdulwahab Khalil, the Syrian Democratic Council’s (SDC) representative in Damascus, downplayed the extent of internal rifts when asked directly about them.

“There are no major divisions within the Autonomous Administration (AANES) regarding integration with the Syrian state,” Khalil told Levant24. He described instead “multiple perspectives within the political and military movements in the region,” acknowledging differences between those favoring closer ties with Damascus and others committed to the idea of a “Kurdish Syria” and PKK ideology. Still, he insisted there is a shared commitment to “sustainable political solutions within the framework of a unified Syria.”

Yet even Khalil’s formulation points to the core tension. The question is not whether the SDF speaks of unity, but whose vision of unity prevails and who ultimately decides. Critics, former fighters, and independent analysts describe a structure in which consensus is often asserted rather than practiced.

Integration or Armed Autonomy

For some observers, the divide is already stark. Berwin Ibrahim, secretary-general of Syria’s Youth for Construction and Change Party, speaking to Levant24 from Lebanon, said the disagreement goes beyond rhetoric.

“There’s a faction supporting integration and a faction refusing to lay down their arms,” Ibrahim said. She linked that refusal to fears of violence as seen in Suwayda or the coast, warning that the trajectory is dangerous. “In my opinion, things are heading for the worst.”

That concern is shared by Syrian human rights activist Dr. Faten Ramadan, who argues that the divisions are both real and deep. “This is evident through conflicting media statements,” she said, noting that some SDF figures speak openly about implementing the March 10 agreement with Damascus, while others claim independence from SDF leadership altogether.

Ramadan identified a fault line between leaders originating from Syria and cadres tied to Qandil, the PKK’s longtime stronghold in northern Iraq. According to her, Syrian figures tend to prioritize avoiding clashes with Damascus and regional powers, while leaders with external ties push to preserve the existing power structure.

Power Beyond the Local Leadership

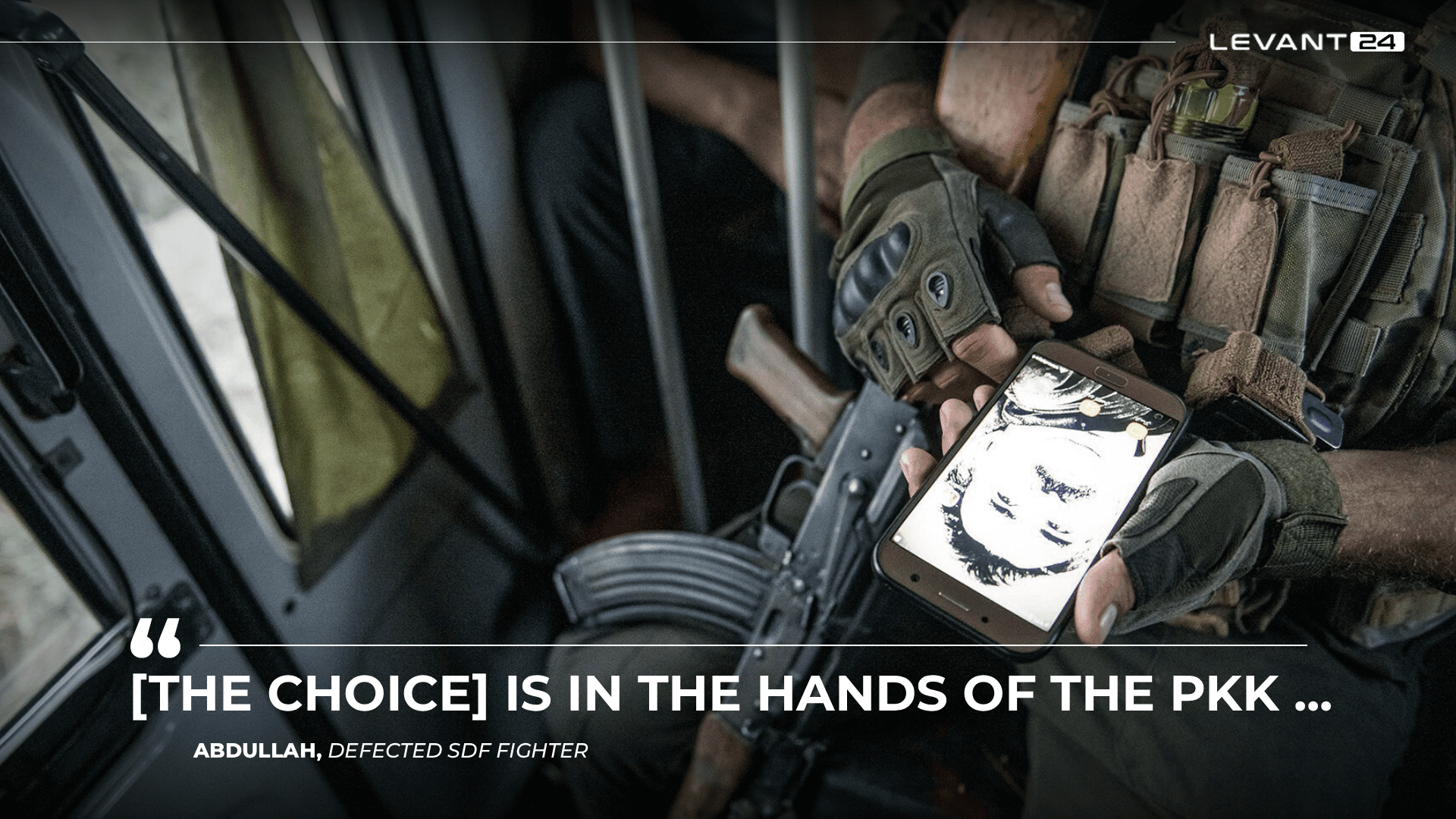

That imbalance is echoed in the testimony of “Abdullah,” a former Arab SDF fighter. In his account, real authority does not rest with the SDF’s visible leadership. “The political decision is not in the hands of Mazloum or Ilham,” he said, referring to Mazloum Abdi and Ilham Ahmad. “It is in the hands of the PKK.”

He described PKK cadres embedded across military and civilian institutions, overseeing everything from oil and trade to tunnel construction. Local administrations, he said, often function under the supervision of figures who have spent decades in Qandil and answer to leaders such as Murad Karilan, a senior PKK commander.

This structure, critics argue, leaves little room for independent political life. Ramadan rejects SDF claims that it represents a unified Kurdish front. “If that were true, it would not have suppressed any political Kurdish activity,” she said, pointing to the repeated closures of offices linked to the Kurdish National Council and bans on party flags in areas under SDF influence.

An Ideology Framed as Governance

Beyond questions of integration lies a broader critique of the SDF’s governing model. Ramadan likened the group’s experience to that of Hezbollah and other ideologically driven militias, describing a system that relies on military force and suppresses dissent, rather than building durable institutions.

“Their survival relies on military force and governance through exclusion,” she said. Despite years of control over oil-rich regions such as Hasakah, Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor, she argued that living conditions and development outcomes remain poor, underscoring what she called the “failure and backwardness of this experience.”

Former fighters describe similar frustrations. Abdullah mentioned discrimination against Arabs, corruption, looting of national resources, and the absence of any long-term vision for northeastern Syria among issues prompting his defection. He also pointed to “open dealings with the Assad regime,” which he said further eroded trust within SDF ranks.

External Pressure and the Limits of Choice

Supporters of the SDF counter that its room for maneuver is constrained by regional dynamics. Khalil pointed to Turkish pressure as a major obstacle to any lasting agreement with Damascus, saying Ankara opposes Kurdish integration with the Syrian state for its own security reasons. Internationally, he said, there is no direct pressure blocking integration, only calls for a comprehensive political settlement.

Journalist Shirwan Ibrahim offered a different reading. He argued that negotiations are largely shaped by the US and its Western partners, with any agreement ultimately requiring American approval. “SDF also fully realizes that it cannot sign any military agreements without American approval,” he said, noting Washington’s decisive role east of the Euphrates.

Ibrahim rejects the idea that a push for an independent Kurdistan drives SDF policy. He said demands for Kurdish independence were formally abandoned by the PKK in 2001, and that current discourse focuses on decentralization within existing state borders. “There is no issue of wanting ‘Kurdistan,’” he said.

Others remain unconvinced, arguing that ideology still shapes practice even if slogans have shifted. Ramadan warned that foreign actors with no interest in Syria’s stability, including Iran and Israel, exert influence to prevent integration, alongside non-Syrian SDF leaders who benefit from maintaining control outside any legal framework.

A Future Caught Between Dialogue and Drift

Recent developments in Aleppo have highlighted the practical limits of dialogue in the absence of clear command arrangements. Renewed tensions and clashes in SDF-held neighborhoods have once again shown how unresolved questions of authority translate directly into insecurity on the ground. For Khalil, dialogue remains the only viable path. He described negotiations with Damascus as complex but necessary and urged constitutional guarantees for Kurdish and other communities within a unified Syria. “Dialogue is the only path to peace and stability,” he said, calling the March 10 agreement a “lifeline” toward pluralism.

Yet voices from within and around the SDF suggest that dialogue alone cannot resolve the struggle over who holds power and on what basis. As long as decisions are perceived to be made by an unaccountable ideological core, skeptics argue, calls for integration will ring hollow.

Internal divisions are not only about strategy or identity. They shape daily life for millions living under SDF rule and determine whether northeastern Syria moves toward reintegration and a political opening or remains locked in a system of parallel authority.

For now, the SDF continues to present a unified face. Behind it, however, the question persists: is the force preparing to fold into a Syrian state, or to preserve an ideological project that keeps Damascus at arm’s length?