Freedom’s Price is a series of articles aiming to shed light on the major massacres that have occurred during the Syrian people’s decades-long struggle for liberation from the brutal Assad Regime. Each article highlights the crimes endured along the path to liberation and the high cost in their endeavor for freedom and dignity. This installment in the series touches on one of the earliest and most brutal massacres perpetrated by the Assads, the Hama Massacre of 1982 where as many as 40,000 were systemically murdered and thousands disappeared, over a monthlong campaign by Hafez and Rifaat al-Assad and their inhumane Baathist regime.

________________________________

The tank’s engine roared as it lurched forward, metal treads grinding against the pavement of the Baroudiya neighborhood. Abdulkarim stood pressed against a wall with nearly 100 other civilians, each marked with a number. When the machine began to crush the bodies of those ordered to lie down, some refused. Soldiers stabbed them instead. Abdulkarim was number 73. When the executions abruptly stopped at 71, he was spared. “I was in a state of psychological panic for more than three months from the horror of the scene and narrowly escaping death,” he later recalled in an interview with New Lines Magazine.

Scenes like this unfolded across Hama in February 1982, during what has become one of the bloodiest massacres in modern Middle Eastern history. For decades, Syrians were forbidden from speaking of it. Today, with the Assad dynasty destroyed, survivor accounts, investigative reporting and human rights documentation provide a clearer picture of what happened 44 years ago, revealing the scale of the crime that would shape Syria’s future and scar a generation.

A City Under Siege

The assault on Hama began on Feb. 2, 1982, when Syrian military and security forces moved to crush an uprising centered in the city. The operation was carried out under direct orders of Hafez al-Assad and involved elite units, including the Defense Brigades commanded by his brother Rifaat al-Assad, special forces, the 47th Brigade and multiple intelligence agencies.

The city was sealed off. Water, electricity and communications were cut. Heavy artillery and aerial bombardment targeted residential neighborhoods, not just armed opponents. Nearly 20,000 troops stormed Hama, while warplanes and tanks shelled densely populated districts.

Entire neighborhoods were erased. Kilaniyya, Asida and Zanbaqi were among those leveled. Nizar, a Hama resident detained during the assault, described indiscriminate shelling that “wiped out” districts that never recovered. He told New Lines that men and boys between the ages of 12 and 75 were dragged from their homes and arrested en masse.

A Murder Machine

What followed went beyond combat. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) estimates that between 30,000 and 40,000 civilians were killed during the nearly monthlong assault, with around 17,000 people forcibly disappeared. According to the organization, it confirmed the names of 7,984 civilians killed and gathered data on 3,762 disappeared, noting that the gap reflects decades of enforced silence and destroyed evidence.

Survivor testimonies describe extrajudicial killings carried out in streets, homes, shops and schools. Nizar recalled men gathered inside a shop on March 8 Street and executed by gunfire. In another incident near the municipal stadium, over 100 young men and women were randomly selected and shot in front of other detainees.

At Hama National Hospital, Abdulkarim said soldiers stormed operating rooms and intensive care units, killing patients under anesthesia. He described bodies piled in the courtyard, some showing signs of torture, moved by bulldozers. The doctors and nurses were spared, but the message was unmistakable.

These acts constitute crimes against humanity, according to SNHR, citing international law definitions that include murder, torture, enforced disappearance and persecution as part of a widespread and systematic attack against civilians. Such crimes carry no statute of limitations and the criminals should be brought to justice.

Erasing the Dead

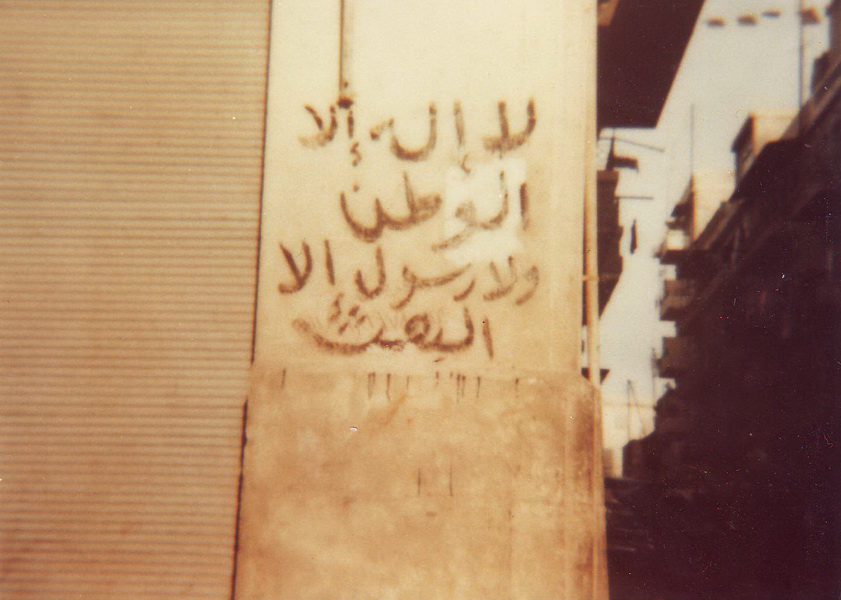

After the guns fell silent, the Assad regime imposed a second assault: silence. Officially, the massacre was reduced to “events” targeting Islamist “terrorists.” Civilian victims were erased from state narratives. Even mentioning Hama could lead to arrest, torture or disappearance.

Fear reshaped daily life and “The walls have ears” became a common warning. Families hid photographs of murdered relatives. Parents avoided telling their children what had happened. For years, Hama’s once-vibrant cultural and flourishing life withered under surveillance and repression.

Internationally, the response was minimal. No U.N. investigation was launched. No Security Council resolution addressed the killings. SNHR noted that senior U.N. officials did not even publicly acknowledge the scale of the atrocity. This absence of accountability reinforced the regime’s sense of impunity, a pattern that would repeat itself after 2011.

A City Remade by Violence

The physical scars of the massacre remain embedded in Hama’s landscape. Razed neighborhoods were rebuilt according to plans imposed by the regime, with government buildings constructed atop former residential areas. Some sites are believed to contain unmarked mass graves.

The human toll was even deeper. Nearly every family in Hama lost someone to killing, detention or disappearance. Yusra, whose father was detained for three years in Mezzeh Military Airport Prison, told New Lines Magazine that he endured torture, including having his fingernails pulled out. He later spoke of sharing a cell with a 13-year-old boy accused of helping “opposition fighters.” The child’s fate remains unknown.

For families of the disappeared, uncertainty stretched across decades. Without death certificates or remains, mourning was suspended. Trauma passed from one generation to the next.

Yet memory survived. Stories were whispered in private. Writers from Hama documented the massacre and its aftermath in novels and memoirs. Photographs taken in secret, including images of destroyed mosques and churches, were hidden for years. Only after the fall of the Assad regime were they publicly displayed.

The Fall of the Regime and an Open File

On Dec. 8, 2024, Bashar al-Assad fled Syria, ending over half a century of dynastic rule. For the first time since 1982, survivors and families could speak openly. Official commemorations of the massacre were held, and families began seeking information about missing relatives through state channels.

This moment was an opportunity and test for Syria’s future. Confronting the Hama massacre, argues SNHR, is essential to understanding how repression was institutionalized and preventing its recurrence. The culture of impunity established in 1982 paved the way for later atrocities, including those committed during the revolution.

In its anniversary report, SNHR called on the new Syrian authorities to formally recognize the massacre as a crime against humanity, establish independent investigative bodies, open security archives and identify mass graves. It also urged international actors to support accountability efforts and pursue prosecutions under universal jurisdiction where possible.

Hama Will Never Be Forgotten

For Hama’s residents, justice is not an abstract concept. It is tied to names, faces and unanswered questions. Abdulkarim still remembers the father who begged soldiers to kill him instead of his son, only to watch his child stabbed to death. Abdurahman Bilal, who lost three relatives in the massacre, told Al Jazeera that for years he could not even look at their photographs.

Remembering Hama is not only about the past. It is about confronting a crime that shaped Syria’s present and warning the world against its repetition. As SNHR concluded, the victims waited over four decades for recognition. Many did not live to see it. Those who remain are still waiting for accountability, justice and the assurance that what happened in Hama will never happen again.