Assad’s systemic campaign of displacement and targeting of the medical sector over 12 years of war has left more than 13 million dependent on external humanitarian aid to meet daily needs and support a severely damaged healthcare system. The situation has been compounded by a series of tragedies: the COVID-19 pandemic, a cholera outbreak, a near-constant disruption of aid, and finally, a series of earthquakes the likes of which the world had not seen in a century. The resulting environment leaves the most vulnerable—women, children, the disabled, and those with chronic ailments such as kidney disease and cancer—at ever-increasing levels of risk.

Healthcare, the Greatest Casualty

The earthquakes nearly completely destroyed an already fragile system. The disaster damaged hospitals in both Turkey and Syria and disrupted logistics; roads were damaged, warehouses and stores of medical supplies were destroyed, and with casualties in the hundreds of thousands, the supplies and facilities that were intact were inadequate, making the region’s healthcare system one of the greatest casualties of the catastrophic disaster.

The Idlib Health Directorate’s Deputy Director Dr. Hussam Muhammad told L24 about those first days, “the situation in Turkey didn’t allow for the follow-up of patients transferred from Syria due to the overwhelming pressure on Turkish hospitals, as well as the damage to the crossing and the medical system.”

While the situation was grave for all in need of care, it was disastrous for those dependent on constant treatment or cross-border care, like cancer patients. Thus, following the aftermath of the February earthquakes, Turkey-based charity Molham Team launched a campaign to provide treatment to cancer patients in the liberated territories of northern Syria.

Muhammad Othman, Director of the Molham Team’s Medical Department, told L24 in an interview, about the importance of establishing and funding viable oncology programs in northern Syria: “Any conflict in the area affects medical treatment and other sectors, but for cancer patients, the impact is much greater because time, as a factor, is more critical than many other issues.” The disruption or delay in treatment can be fatal for such patients who must receive regular treatments over months to treat their conditions.

Ali al-Ahmad is one of the hundreds affected by the current situation. As the father of a child with cancer, his family is directly impacted by the disruptions and lack of treatment. He lamented that, “Due to the war, no cancer treatment reaches the liberated areas, and the only road to treatment, Bab al-Hawa crossing, is closed,” telling L24, “I hope someone can help, or at least open the crossing or secure treatment.”

Hematologist and department head for the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), Dr. Ayham Jamu, explained, “In times of crisis, such as the current situation of closing Bab al-Hawa border crossing or stopping the crossing to Turkey, we find that we have a significant deficiency in resources due to the lack of chemotherapy treatments for all types of cancer, and the lack of radiotherapy or immunotherapy.” Medical practitioners in the region, like Dr. Jamu, recognize that cultivating local services is paramount to serving people and saving lives.

Importance of Integration

To address such challenges, healthcare providers have worked to establish local facilities capable of meeting the needs of general and specialized medical cases. The first cancer center in the liberated areas opened in Idlib in 2018 and is the primary center for cancer patients in northwest Syria until today, serving an average of 500-600 patients per month. While not the first, Othman stressed that Molham’s initiative was “very significant, as it aims to establish a specialized medical center for cancer patients whose primary objective is to ensure patients receive treatment and reduce the number of deaths on a daily basis.”

What is unique about the more recent projects, said Othman, is the focus on self-sufficiency. This phase hopes to lay the foundation for a new and revitalized medical system. “We’ve launched the ‘Save Them’ campaign for cancer patients to sustain medical work and not just provide urgent assistance. The goal of the campaign is to establish a complete integrated center for these patients and ensure its continuity with the concerned parties in the region.”

The view of the need to partner with local and regional organizations and medical practitioners is one shared by King’s College London’s Abdul Kareem Aqzez, a contributor to both the Syrian Public Health Network (SPHN) and the Research for Health System Strengthening in Syria (R4HSSS). Aqzez believes that international donors, both state and private institutions, will be more beneficial through more coordination with the local governmental and medical institutions operating in the region.

“The role of international organizations is sensitive,” Aqzez told L24, “but I think that these organizations rely more on planning for pure humanitarian work without giving priority to local priorities, which are local organizations and local health governance, such as health directorates, which have a greater ability to identify local health priorities.”

Much of this apprehension comes from what some like Aqzez refer to as the “politicization of healthcare.” He explains that the liberated north has two health ministries, one under the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) and the other under the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG). “I believe,” he explains, “that the lack of international recognition of these ministries makes it difficult to deal with them directly on an international level because some donors will be concerned about dealing with them.”

Without unilateral recognition representative of the reality on the ground, which is that these ministries do, in fact, function as public service health facilities, there can’t be any substantive and enduring contributions to the healthcare sector in northern Syria.

Success in Sustainability

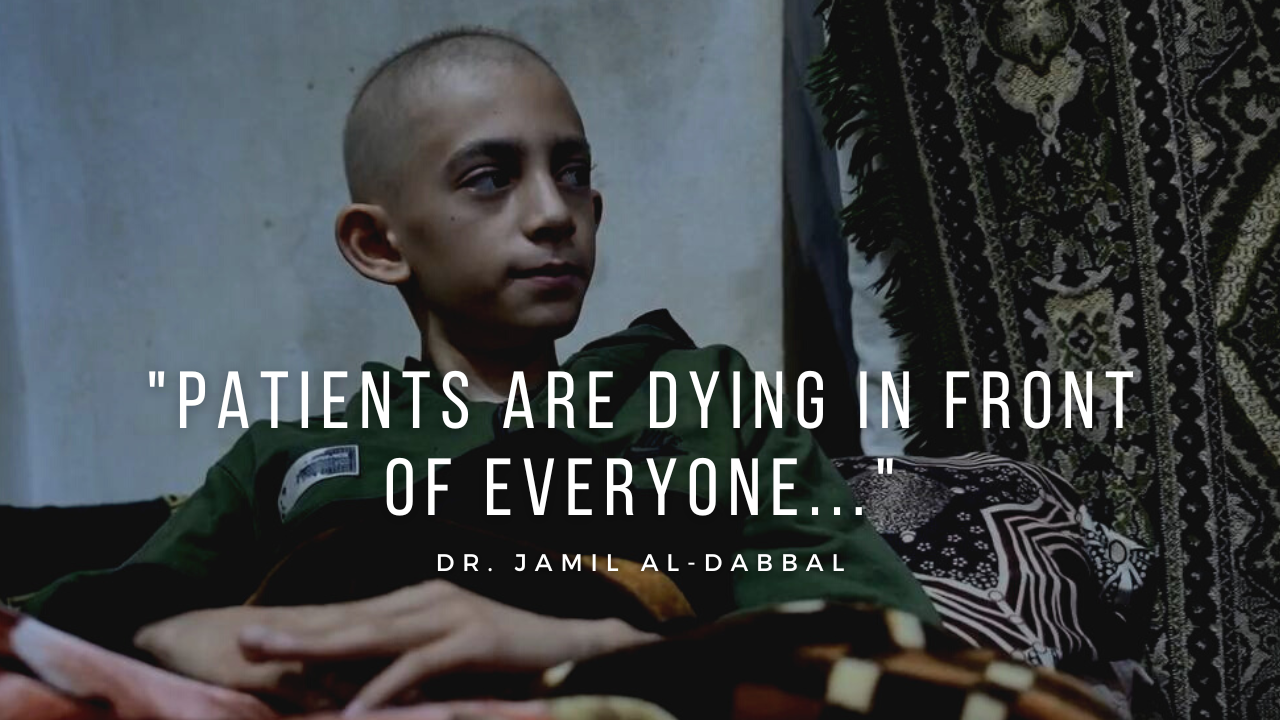

While the local healthcare services fulfill the roles of governmental health services, they don’t possess the resources of a state due to war, physical and economic besiegement, and ongoing disasters such as the earthquakes. “The absence of an integrated healthcare system is one of the biggest risks here,” says Dr. Jamil al-Dabbal, an oncologist and hematologist working in Idlib, “we don’t have the resources of a state that can provide complete treatment for cancer patients. We don’t have radiotherapy but have many patients who need it. Patients are dying in front of everyone due to the lack of radiotherapy.”

While resources and access to equipment and facilities have been on the decline recently, especially in the aftermath of the earthquakes, the number of those in need of vital care and specialized treatment has been on the rise, as Dr. Dabbal observes, “The region has seen a steady increase in the number of cancer patients, with an average of two to three cases diagnosed daily.” Molham’s Othman attributes the increase in volume to physical, fiscal, and psychological stressors, noting, “the number of infections increases more in conflict zones… due to many factors, most notably the psychological and living factors, lack of appropriate diagnostic equipment, and unavailability of treatments in these areas.”

Such shortages are not only logistical issues caused by war and disasters but also those imposed upon the region by external forces: Assad, Russia, and the antiquated and ineffective mechanisms that make providing aid to those in need “impossible” due to solely artificial political constraints. “Issues with equipment, logistics, and medical staff, as well as the inability to repair them,” says Deputy Director Muhammad, “are due to the ban on their entry,” pointing out the isolation of northern Syria through military and political siege is one of the greatest hindrances to maintaining the medical sector.

The key to long-term success is what Othman refers to as the “sustainability of medical work.” Part of the issue lies in the expensive nature of cancer treatment, as one NGO worker told a colleague they could fund, “500 pediatric patients with the cost of one cancer patient.”

Aqzez suggests several solutions: “…this support is not permanent, so we must look for new models of health financing.” Revenue could be generated, he says, from patients by charging nominal fees for nonessential services like MRIs. Healthcare professionals could also serve as a source of limited funding via licensing and certification fees and dues, while community-based privatized funding could be sourced, both internally and externally, from donations by individuals and civil societies. He concludes, “As for long-term solutions, we must create health financing models that depend on either group taxes in the region or on a government capable of funding the health sector.”

Delay is Death: Urgent Action Needed

As of writing the Bab al-Hawa administration announced, “To our patients with cancer who need treatment in Turkey, we inform you … your transit movement to Turkey will be resumed through the Bab al-Hawa crossing.” While welcome, the news of the re-opening comes after nearly four months of cessation, during which many patients have been without life-saving treatment, some of whom may have died due to such disruption.

The collapse of medical infrastructure in northern Syria would result in a humanitarian crisis and likely a wave of “medical refugees,” forced to go abroad seeking lifesaving medical care. Rebuilding the medical sector is crucial to address the urgent health needs of millions of refugees and IDPs and a communal obligation on humanitarian and international agencies.

It’s imperative that such organizations, governments, and individuals come together alongside the existing ministries, institutions, and organizations, already in operation in Syria, to revitalize and strengthen the medical sector. Consequences of neglecting cancer treatment may prove devastating and deadly to such vulnerable communities, thus urgency in addressing the issue must occur to save lives and alleviate suffering.