Written by Abdulwahab al-Khateeb

A Weapon of the Revolution

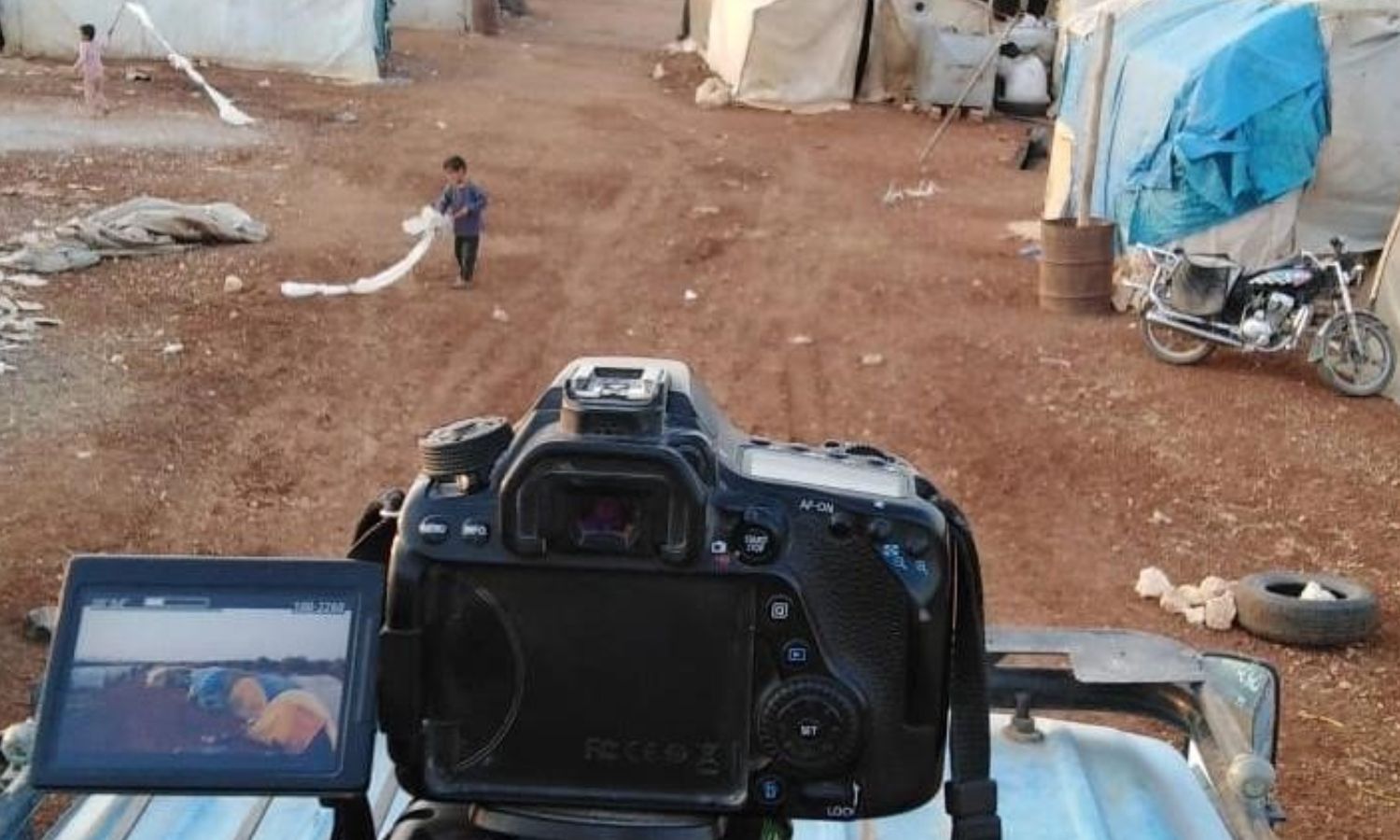

From its beginning, over 11 years ago, media played an important role in showing the struggles of the Syrian people and documenting the many crimes of Assad, Russia, Iran and their allies. From leaks of mass graves, executions, torture and other crimes against humanity, to the citizen filmed videos distributed via social media, journalism, whether photo, video or written has been one of the most potent tools in the arsenal of both the Syrian people and their enemies from the tyrannical and oppressive regimes.

Najib Al-Khalil, a journalist from Idlib, who studied at the Faculty of Media in Damascus 2011, but had to come back to Idlib because members of the regimes` prosecution, spoke to L24, remembering the media work of those early days, “There were advantages of the unregulated media of the past, news spreads faster, the decentralized nature made it difficult for the regime to dry up the sources of media, documentation of the events of the Syrian revolution and regime crimes, and bringing humanitarian support from all countries of the world.”

Yet just as other tools, weapons and groups have become regulated and codified through the decade of struggle, so too has media. The early days of the Syrian uprising saw people armed with shotguns, pistols and whatever they could find, resisting oppression and defending their families, homes, neighborhoods, cities, towns and villages as individuals or small groups. Over time people saw the need to organize, coordinate and operate under a unified structure and rules so as to avoid chaos and unify ranks and vision. The Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), which is governing the Greater Idlib province, introduced new regulations in the last years, which will set the standard of how media freedom will be perceived in future.

“Some of the defects [of those days were], emotion overcomes reason, the rapid spread of rumors and propaganda, doubt about sources of news and credibility, the ease of security breaches by the Assad regime, and hastening to pass judgment on this or that party”, Al-Khalil continues.

A Need for Regulation

The media shouldn’t be a disruptive force spreading rumors, confusion and propaganda as often as facts and truth. The only way to ensure this is through the ratification of laws that ensure that those who produce, oversee and consume the media know their rights, limitations and obligations towards one another and have a system in place to protect and enforce them.

L24 had the chance to look over a 27-page draft of media regulations, provided by the SSG`s Press Affairs Directorate, and spoke with the Khaled Shaqfeh, the head of the directorate who provided some background on the initiative, “The laws were first introduced over a year ago, after more than 12 meetings between senior media figures and legal specialists and media organizations and press institutes,” the regulations from those meetings have slowly been refined and implemented over time, Shaqfeh commented on the inclusion of journalists alongside the government saying that, “… it was important to establish laws regulating this process between all parties…”

Fayez Al-Dughim, another journalist in Idlib, whose media career began as an activist in 2013 and works currently for Syria TV, spoke with L24 on the topic, “I attended a meeting [with the government] and saw that the general issues between the government and journalists are agreed upon and undisputed, such as respecting the principles of the Syrian revolution and not offending society and others, but there are differences regarding the details, and I cannot express my opinion on the law before its presented.”

A Period of Transition

As Al-Dughim mentioned the laws have not been fully implemented, the document L24 received and the rules discussed in dozens of meetings are not finalized, the government seems to be very cautious in its approach and implementing the system slowly, to assure that all parties are given their due rights.

Al-Khalil, mentioned, “after 11 years of the Syrian revolution, the regulation of media work is still in its infancy, especially since most of the workers in the press are rebellious, non-academic youth.” to which Al-Dughim adds, “it is certain that we are all for the transition from a chaotic state to an organized one, but we are in a phase when laws have begun to limit freedom of the press.”

According to the Kurdish agency North Press, US journalist Lindsey Snell said, that authorities “routinely arrest journalists in their areas. They’re held in terrible conditions,” she continued that the government “instituted a crazy accreditation process to keep tighter control over what journalists do in their territory. I’ve seen some of the press cards the ‘salvation government’ has issued, and they’re valid for six months or less.”

Freedom of the Press

L24 asked Shaqfeh if the Press Affairs Directorate was aware of these concerns, “after applying for a press card, and becoming familiar with the code of conduct journalists can work in, and photograph, any area or official institution in Idlib. …the freedom of the press in Idlib is greater than others in the region, and none of the surrounding countries reaches this level of freedom. This is something you do not find in the SDF and regime areas where material must be submitted to the security forces prior to production and before distribution (after filming).”

Al-Khalil seemed to agree with this assessment, when L24 asked if the current situation and trajectory, under proposed regulations, constituted a threat to press freedoms he said, “It’s not without some minor inconveniences, and we understand it because we are living in a state of war, [but] if we compare the freedom of the media in Idlib with the countries of the Arab Spring revolutions, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Algeria, we find that Idlib surpasses them all in freedom of the press.”

However not everyone in the field holds the same optimistic view, Al-Dughim responded, “In Idlib, there’s partial, not absolute press freedom… we’re allowed to address certain topics and prohibited from discussing other specific topics. Broadly, we can’t call it freedom, yet compared to other Syrian regions it’s considered a kind of freedom.

Conforming to International Norms

The reality seems to be similar to other countries where needed regulation is often viewed on a spectrum rather than a single monolithic perspective. While unable to discuss in full, from the draft L24 received, it was evident the main concerns of the regulations were to ensure that the practices of media apparatus were in line with Islamic law and the cultural mores prevalent among Syrians, and that all parties from citizens, to journalists, the government, and even outside agencies and individuals, had a shared point of reference for established guidelines and clear recourse for maintaining their rights.

“There must be controls for journalism so that it does not fall into practices that offend society.” Fayez Al-Dughim opined and it seems that the majority agree that there do, in fact, need to be a set of strictures that provide structure for both journalists and the government.

Al-Khalil concludes, “I consider this a necessary step. The relationship between the journalist, activist and the ruling authorities must be based on legal foundations and not whims and personal goals. The law defines the rights and duties of the journalist. Today, we are in dire need of a law that regulates media work, like other countries of the world.”