A fighter steadied his phone against the barricade of concrete slabs and sandbags shielding him and his companion as they stood guard overlooking Assad-occupied Saraqib City in the distance. It was May 2024, months before the whirlwind 11-day campaign that would overturn over six decades of Assad family rule. The city spread out below him, quiet in the morning haze. Beside him, a fellow member of the Red Bands unit watched as he pressed record.

“We will enter it,” Abu Bakr al-Shami told the man next to him, recalling the moment later in an exclusive interview with Levant24. “And we will enter Damascus, God willing.”

It was not a prediction made lightly. The Red Bands were one of the most elite units within Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The unit played decisive roles on critical fronts like Aleppo and Hama, with members like al-Shami having devoted years in training. The remark reflected a belief that had taken root across many fronts in the northwest: victory was no longer a hope, but the expected outcome of a long, disciplined project. What unfolded that December stunned observers around the world, but those inside the preparations describe the outcome as the result of patient work rather than a mere confluence of fortuitous events.

From reorganizing fragmented groups to retraining depleted units after catastrophic losses, to building new weapons from scratch, revolutionary forces spent years reshaping their military posture. Interviews with commanders and fighters show a methodical effort that reached from political leadership to village councils, and from advanced workshops to remote frontline camps.

These accounts reveal a layered strategy, making the rapid victory of December 2024 possible. While dramatic battles and sudden breakthroughs marked the final days, the groundwork had been set long before.

Shifting Morale and the Return of Cohesion

The first challenge was psychological. Defeats in 2019 had devastated front lines and displaced thousands. Brig. Gen. Jamil al-Salih, commander of the 74th Division, former commander of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) affiliated Jaish al-Izzah, described the years that followed as a struggle to rebuild not only capability but confidence.

“The biggest difficulty in preparing, frankly, was the issue of the low number of fighters and compensating for the losses incurred in the 2019 battles,” Salih said in an interview with Syria TV. “Convincing our people that we would not retreat again after another battle and losses, convincing the youth, convincing the public, this was very difficult.”

Those years became a test of endurance. Fighters had to return despite fatigue, a sense of abandonment, and the knowledge of how unequal the battlefield had been against Russian airpower and heavily equipped regime units. According to Salih, bringing men back to the front lines required direct engagement, continuous reassurance, and a clear message that future battles would be fought differently.

al-Shami offered a similar perspective from within the Red Bands. Long preparations, he said, instilled patience and sharpened determination. “We were certain that we would be victorious, an unwavering belief,” he told L24. “Our goal was clear, our preparations were complete, and we relied on God.”

That confidence did not appear overnight. It grew through repeated drills and cumulative adjustments. Small units learned to adapt to battlefield realities. In earlier years, for instance, a single machine gunner or rocket launcher operator could be the only one trained on a weapon, so a single casualty could cripple a unit’s entire capability.

“This problem was addressed by providing basic training to all fighters on the PK machine gun and the rocket launcher, followed by specialized training,” al-Shami explained. He described this as only one example of “many problems” corrected in the last two or three years before the decisive operation.

The improvements became visible. Morale rose. Units grew physically stronger and more cohesive. Fighters began volunteering for frontline roles in higher numbers. Committees that surveyed readiness in the days before the launch found what al-Shami called a “huge turnout,” with men eager to be assigned to the front rather than support positions.

Reconstruction of the Military Architecture

Prior to the liberation, commanders began a deep restructuring of leadership and coordination. The system of scattered factions operating with limited cooperation was no longer sustainable. Unification efforts gained momentum following, a historic, meeting in Jabal al-Zawiya between the leadership of the major revolutionary factions, including Syria’s current president, then known as Abu Muhammad al-Jolani. Those in attendance formed the nucleus of the coalition that would liberate the country five years later.

That unified command was the Fath al-Mubin Operations Room (FMOR), which became the central coordinating body, linking all major fronts in the northwest. The Liberated Areas were partitioned into several main fronts and axes, all linked to the centralized FMOR, with intrafaction coordination prioritized as key to defense and military ascendancy going forward.

Salih, who witnessed the restructuring from within, offered more detail. After the losses, the number of experienced commanders and elite fighters had declined sharply. This meant the next battle had to be decisive and could not be attempted without comprehensive preparation.

“You could no longer enter a battle unless you were very well prepared and equipped,” he said. To ensure the highest levels of preparation, the revolution’s first Military College was established in Idlib in 2021 and graduated its first class of officers in September of the following year. Training continued both in the classrooms and in the field, in the trenches and on the front lines.

The north witnessed a full renaissance that touched every specialty. “Training plans were developed for all specialties: night operations, night training, sniper operations, reconnaissance, aviation operations, artillery, tank drivers and gunners, all weapons,” Salih explained. Additional courses refreshed the skills of older crews and trained replacements. This phase also required unifying command structures. “We tried to close down small operations rooms and military groups and make a single military council, a single operations room,” he said.

Areas were divided into sectors across the coastal region, the Ghab Plain in Hama, and Jabal al-Zawiya in Idlib, each with assigned units and leadership. Defensive positions were fortified, tunnels and trenches were dug, and frontline towns were secured against regime advances. The operations room also improved discipline and internal oversight, which greatly helped reduce mistakes that had previously resulted in losses.

Beyond the Battlefield

Perhaps the most unexpected element of the preparations was the degree to which they extended beyond the military. Civil administrations, ministries, police forces, and local councils were pulled into a broader plan that anticipated the responsibilities of governance once regime areas fell.

Without the strong civil institutions helping to oversee logistics and administering civil, economic, and security affairs, the military operations would have likely become overburdened and bogged down as new areas were opened, slowing momentum and leaving liberated communities vulnerable to chaos and disorganization in a power vacuum.

“The preparation was not just at the military level. It extended to the ministerial level as well,” Salih said. He recalled detailed planning sessions covering essential logistics, municipal services, wheat distribution, and public safety. The Idlib-based Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) ensured that its ministers and local officials were prepared for rapid deployment to secure government buildings, maintain order, and reassure civilians in newly entered areas.

“We had to protect government offices, institutions, and people’s money. We had to reassure the residents,” Salih said. He described a message delivered to fighters: the towns and cities they would enter were not enemy territory, but communities they belonged to.

Local populations also contributed. One example of this organized public involvement came through the emergence of the Popular Resistance Brigades. Formed under SSG auspices and coordinated with HTS, the Popular Resistance Brigades added a tribal and civilian-driven layer to the wider preparation effort. The movement emerged from local initiatives and grew into organized units across towns and villages in Idlib and its surroundings.

Its members built fortifications, reinforced rear defensive lines, and supported fighters through monitoring positions and logistical aid. The Brigades relied on community donations, including crowd-sourcing campaigns fully equipping fighters. Their organizers described the project as a way to align public effort with military unity on the fronts.

Volunteers in villages were also prepared to set up checkpoints during the advance and provided assistance during the transition. The work remained deliberately quiet. There was no public announcement, partly to maintain operational security and partly to avoid raising expectations prematurely.

Small Operations with Strategic Purpose

Signs of long-term planning appeared even earlier. In early 2023, more than a year and a half before the final campaign, revolution factions intensified their use of hit-and-run raids across regime lines. These were not large offensives but targeted actions by elite teams, trained to move at night, avoid detection, and strike quickly.

Hamza al-Firdawsi, a former FMO commander, told Levant24 in a January 2023 interview that new doctrines and tactics were implemented as early as 2022. Over a couple of months in 2023, 14 special operations against the Assad regime were conducted. “The goals of these missions,” says Firdawsi, “[were] to test the enemy’s defensive capability, increase combat readiness of our forces, which will prepare them for larger operations in the future.”

These early operations appeared modest, but they served as training grounds for the offensive tactics that would be applied later on a larger scale. As Firdawsi mentioned, “There is no doubt strategies have been planned for future implementation; all [we] need is time and the necessary capabilities… we are in Idlib, but our eyes are on Damascus, and we will reach it, God willing.”

Logistical Independence and Self-Reliance

A crucial shift came with the transition from reliance on captured weapons to domestically produced arms. During the early years, revolutionary factions relied heavily on seizing ammunition or equipment during raids. After 2019, the reduction in major clashes meant captured supplies dwindled. “Now you have to be forced to manufacture weapons,” Salih said. “This phase is not just about preparing fighters. It is about manufacturing mortars, rockets, rocket launchers, and drones.”

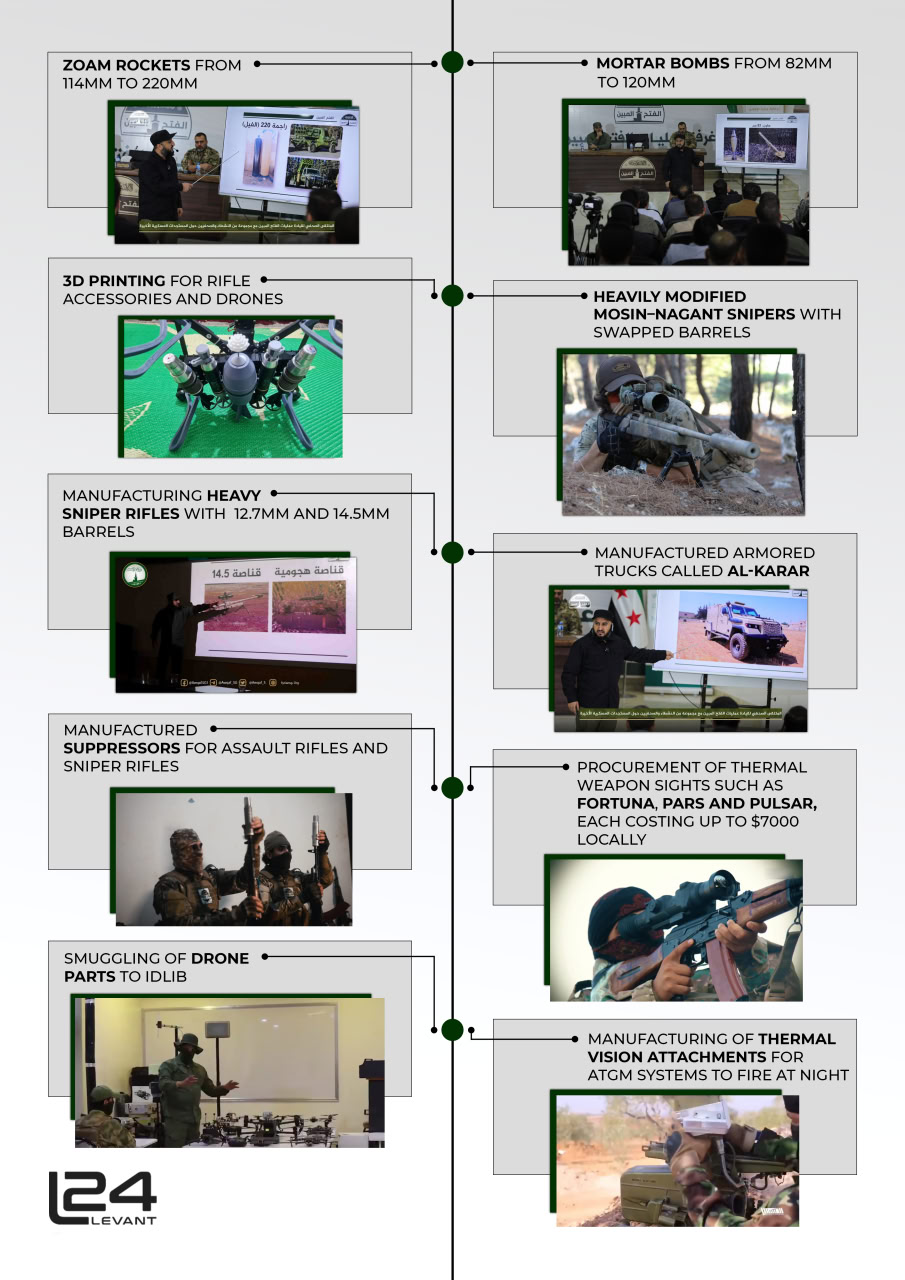

To ensure adequate defense and preparation, a domestic arms industry developed in the north. Armored vehicles, sniper rifles of various calibers, rockets, rocket launchers, mortars, reconnaissance and weaponized drones, as well as munitions for small and medium arms, were all manufactured locally.

Firdawsi noted that workshops across the region developed new capabilities, from small munitions to drone systems. “Manufacturing of weapons and financing ammunition,” he said, “[took] the lion’s share of the budget,” adding that resources were tightly managed to ensure efficiency. Commanders describe this manufacturing capacity as essential to sustaining long campaigns without external supply guarantees.

The Final Months Before the Breakthrough

By mid-2024, regional dynamics also created an opening. Russia was absorbed by the war in Ukraine, while Israel’s strikes on Iran and Hezbollah left Assad’s strongest backers weakened and distracted, reducing their ability to reinforce him at a decisive moment. Fighters sensed a shift.

Al-Shami noted that the war between Israel and Hezbollah had drawn Hezbollah’s attention away from the Syrian front, while Russian forces were heavily committed in Ukraine. Confidence spread through the camps.

“Morale was high, the numbers were high, there was reliance on God, and all necessary precautions were taken,” he said. Committees surveyed fighters, medical readiness, and logistics in the days before the launch. The response was overwhelming, he added, with men competing to be placed at the front.

When the campaign finally began, many inside the revolutionary forces expected a long fight. Instead, the regime collapsed in a matter of days, and by December 8, the revolution announced victory. “It is true we did not expect it to be this fast,” Salih reflected.

Years of organization, training, and planning by the revolution were mirrored by Assad’s forces with what one analyst called “ years of poverty, corruption, and cronyism,” creating a “hollow army” and a perfect storm for the well-trained and disciplined revolutionary coalition, supported by a parallel system ready to govern the moment the front lines shifted.

That day in May, Abu Bakr did not predict the timeline, but he believed the direction was set. Months later, that quiet guard post became one of many from which fighters surged forward. The 11 days that shocked the world were shaped by years of preparation, carried out in camps, workshops, and operations rooms across the liberated areas.